Student Image Challenge 88

April 23, 2021

Student Image Challenge 89

April 30, 2021The ultrasound diagnosis of ovarian torsion

AUTHORS

Dana Nedelcu 1, Ilinca Dobrin 1

1. Regina Maria-Ponderas Academic Hospital, Bucharest, Romania

Dana Nedelcu 1, Ilinca Dobrin 1

1. Regina Maria-Ponderas Academic Hospital, Bucharest, Romania

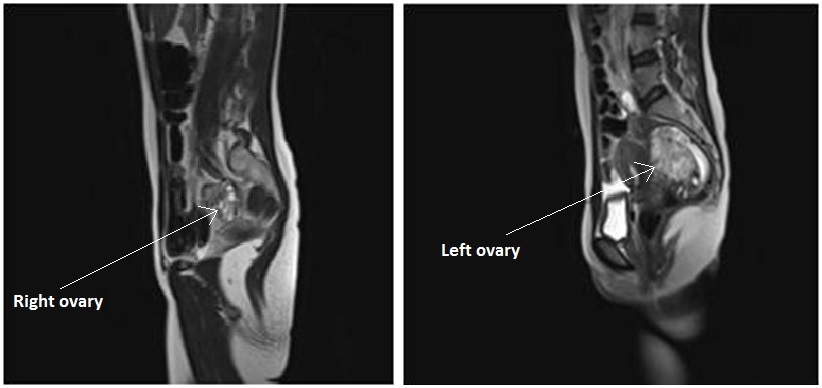

Fig. 10 - A pseudotumor appearance of the left ovary located retrouterine, measuring 55 x 57 x67 mm, with intensely inhomogeneous structure, vascular congestion at the upper pole of the left ovary, medium amount of intraperitoneal fluid and no abdomino-pelvic lymphadenopathy. A normal aspect of the right ovary

1Abstract

Ovarian torsion is an uncommon but significant cause of acute lower abdominal pain in women, especially at reproductive age. It represents a condition where the adnexa rotates around its vascular axis and this can lead to ischemia and subsequent necrosis of the ovary. The clinical picture is non-specific which implies a difficult diagnosis and, thus, the clinical suspicion is very important for an early recognition. In order to preserve the ovarian function and to reduce morbidity, prompt diagnosis and management are essential. This case report illustrates the diagnostic algorithm based mainly on ultrasound and emphasises the key role of contrast enhanced ultrasound for assessing ischemia in ovarian torsion.

2Case history

A 29 year old woman with a history of thrombophilia and caesarean section for intrauterine fetal death, presented to the emergency room for constant and severe pain in the left iliac fossa and metrorrhagia. The patient had no other gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms. On examination, she was afebrile, with abdominal tenderness and her vital signs were within normal limits. Speculum examination demonstrated a small amount of blood coming out of the cervix and bimanual pelvic examination demonstrated a voluminous tumor of about 7 cm located retrouterine and to the left iliac fossa, sensitive to palpation.

3Imaging findings

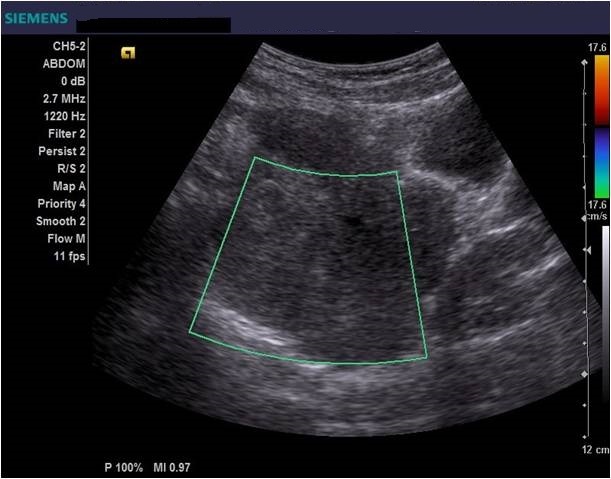

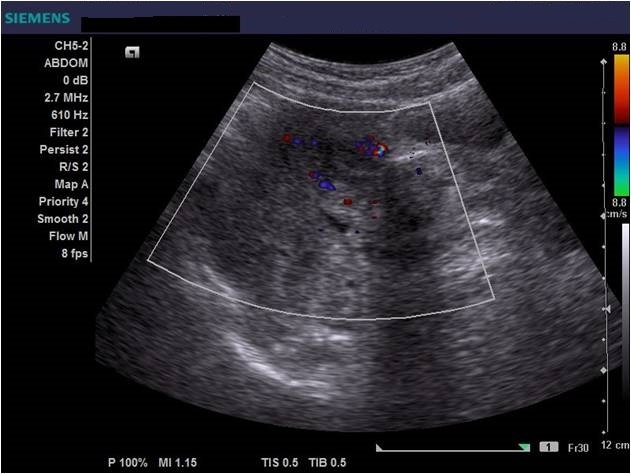

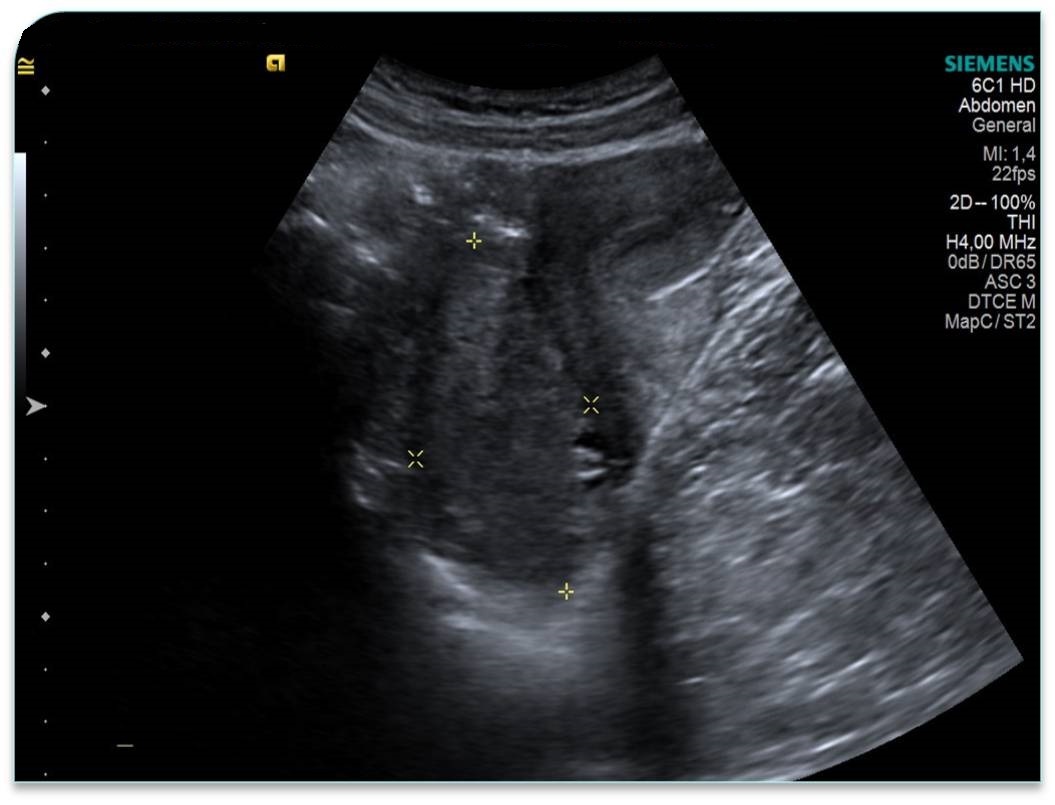

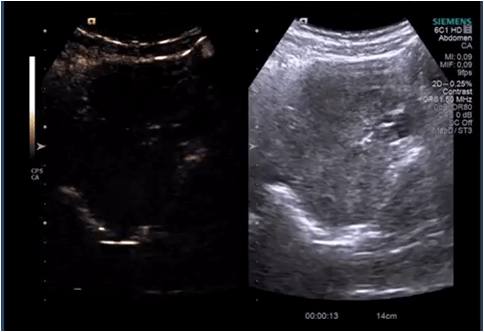

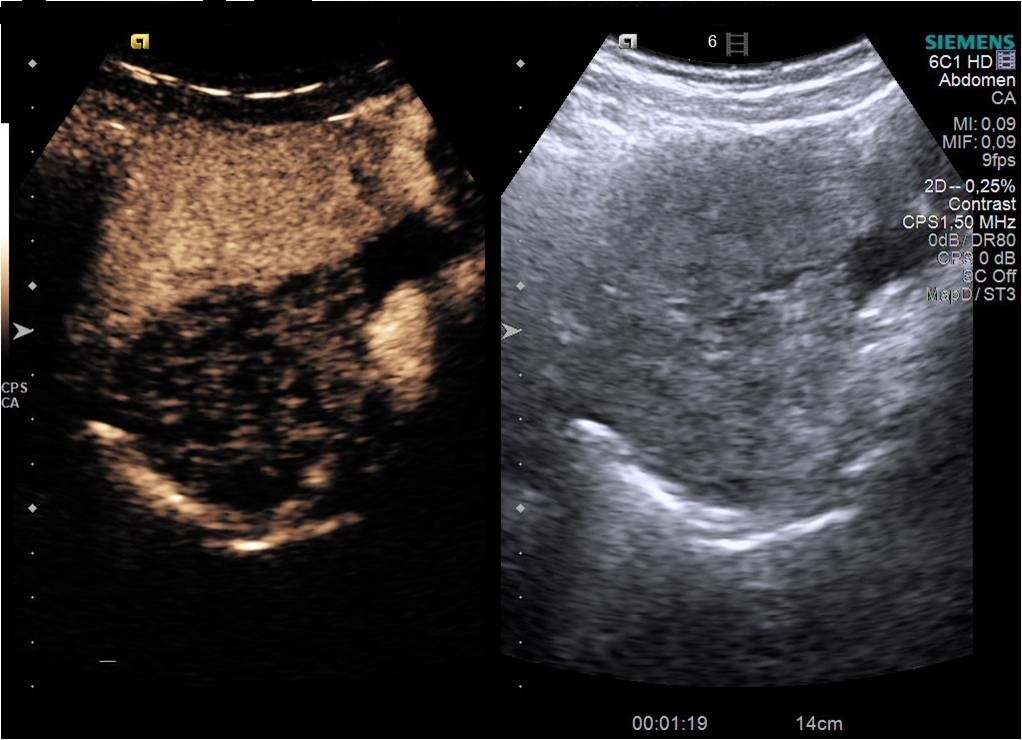

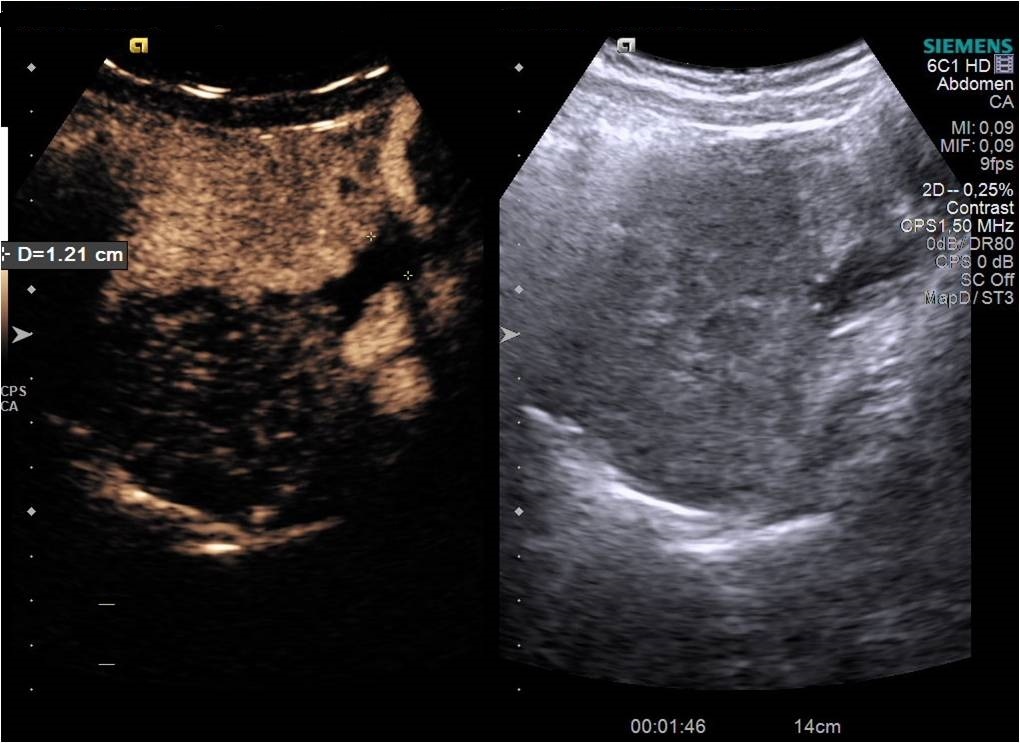

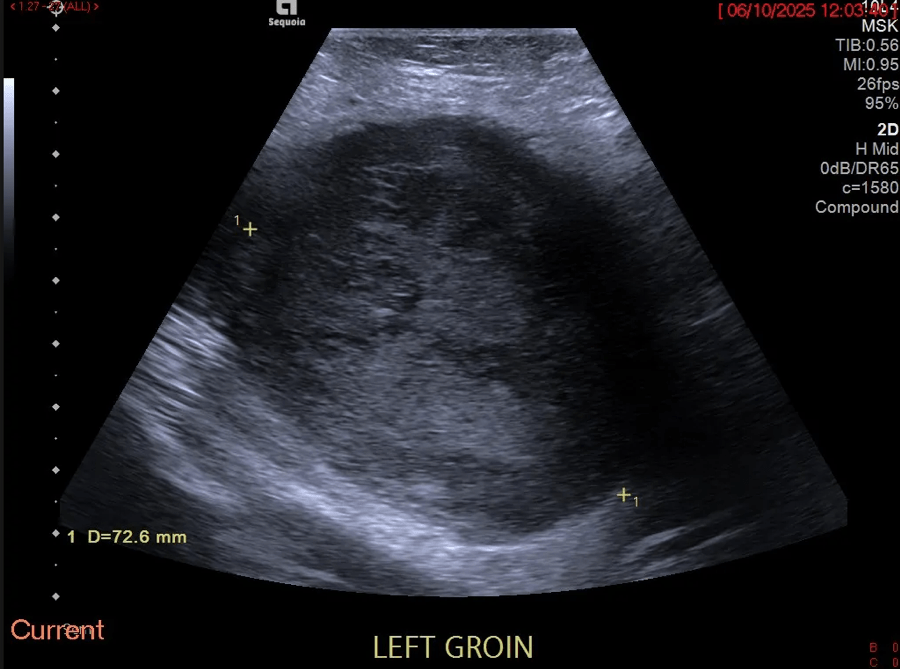

Diagnostic algorithm included in the first instance a transvaginal ultrasound which revealed a normal right ovary while the left ovary could not be visualized. In addition, there was a retro-uterine, irregular hypoechoic mass measuring 71 x 45 mm, with Doppler flow present and a small amount of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas (Fig. 1 and 2). Transabdominal ultrasound revealed the same findings (Fig 3, 4, 5). The patient was admitted and was re-evaluated the same day in order to also perform a contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and seek an expert medical opinion. B-mode ultrasound showed a large left ovary extended into the pouch of Douglas with a heterogeneous architecture (Fig. 6). On CEUS, in the arterial phase, the mass and the left ovary were hypoenhanced compared to the uterus, with slow, delayed perfusion of the ovarian tubal extremity, which still retained a normal architecture (Fig. 7). In the late phase, the ovary showed inhomogeneous enhancement with discrete wash-out (Fig. 8 and 9). Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the ultrasound findings: a pseudotumor appearance of the left ovary located retrouterine, measuring 55 x 57 x 67 mm, with an intensely inhomogeneous structure, vascular congestion at the upper pole of the left ovary, a medium amount of intraperitoneal fluid and no abdomino-pelvic lymphadenopathy (Fig. 10).

4Diagnosis

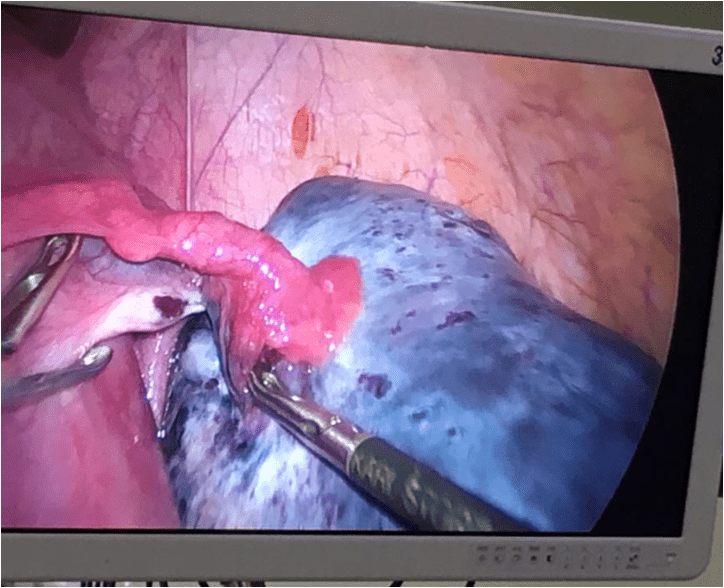

A preliminary diagnosis of left ovarian tumor as a source of ovarian malposition and incomplete ovarian torsion was made. An emergency laparoscopy was performed and intraoperative findings were suggestive of a chronic ovarian torsion with diffuse macroscopic changes (”blue-black” ovary) and the surgical team performed a left sided oophorectomy (Fig 11). Pathology revealed no signs of malignancy, with massive ovarian edema associated with areas of necrosis and infarction, secondary to possible ovarian torsion.

5Discussion

Ovarian torsion represents a gynaecological emergency that can affect women of all ages, but is most commonly seen in women of reproductive age (1). In patients with acute pelvic pain, ovarian torsion was diagnosed in 2.5-7.4 % of cases undergoing emergency surgery (2). Taking into consideration that the diagnosis can be misled and not all the cases are referred to surgery, the prevalence can be underestimated. Typically, the torsion is unilateral and involves usually ovarian masses over 5 cm or larger (3). More frequently, the torsion occurs in the right ovary as the sigmoid colon is limiting the mobility of the left ovary (4). Risk factors include pregnancy, ovarian stimulation, malformed fallopian tubes, tubal ligation, previous pelvic surgery and ovarian masses (5). The latter represents the cause for over half of ovarian torsion cases and include benign and malignant ovarian tumors. Among all risk factors, dermoid tumors are most common.

In this case report, the patient had the left ovary affected despite the right-sided predilection and a history of previous pelvic surgery. Symptoms of ovarian torsion are non-specific but the classic presentation includes acute sharp or stabbing pain located unilateral in the lower abdomen, often with nausea and vomiting and even vaginal bleeding, symptoms highy variable depending on the extent of ischemic syndrome (6). Physical examination can reveal abdominal tenderness and a palpable pelvic mass. In some cases with incomplete torsion, patients can experience severe intermittent pain with asymptomatic periods (6). The clinical picture can bring into question other causes of acute abdomen such as ruptured follicular cyst, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, hematosalpinx, appendicitis and diverticulitis (7). In our case, the patient had the classical clinical presentation and in the first instance, the diagnosis was of an ovarian mass leading to torsion.

The diagnosis can be challenging and thus, a comprehensive approach is essential. Imaging studies play an important role for patients with suspected ovarian torsion. The first-line imaging modality in the diagnostic algorithm is pelvic ultrasound and also color Doppler analysis to assess the ovarian blood supply and the degree of vascular compromise (8, 9). Moreover, an emerging modality with vast potential is CEUS, especially when considering the limitation of colour Doppler (10). In the second-line, imaging modalities like computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used when ultrasound findings are nondiagnostic or inconclusive (11). But in order to establish an accurate and definitive diagnosis and to avoid further damage of the ovary, emergency laparoscopy should be performed after a thorough and rapid examination.

Ultrasound is the most important investigation for ovarian torsion and findings may vary but the most constant finding is an unilateral ovarian enlargement (> 4 cm) secondary to impaired venous and lymphatic drainage (12). Other sonographic features include: variable echogenicity, heterogeneous ovarian stroma caused by edema and/or hemorrhage, peripheral cystic structures (“string of pearls” sign) due to the displacement of follicles subsequent to ovarian edema and venous congestion, often a coexistent mass which can be cystic, solid or both and sometimes intraperitoneal free fluid (1, 11, 12). In chronic torsions the ovary has a complex, pseudotumoral appearance with chronic ischemia alternating with hemorrhagic areas. Colour Doppler sonography may be helpful to evaluate the viability of the ovary but the interpretations can be highly variable and some authors dispute its usefulness (11, 13). Traditionally, the presence of blood flow indicates the existence of permeable vessels and thus, that the ovary may still be viable. However, a normal flow cannot rule out ovarian torsion and cannot exclude intermittent torsion. This is consistent with the findings in one study where normal Doppler flow was found in 60% of surgically confirmed cases (9). Sometimes, the classical ”whirlpool” sign (twisted ovarian pedicle) can be observed. Although colour Doppler has some limitations regarding the detection of slow flow and the tissue movement that can simulate the presence of vascular flow, it can still be useful in determing the preoperative viability of the ovary. In our case, ultrasound showed an enlarged ovary, measuring over 4 cm, with a heterogeneously architecture and a moderate amount of intraperitoneal free fluid. Colour Doppler ultrasound demonstrated blood flow of the left ovary and adnexal mass, and thus resulting in a false negative diagnostic of ovarian torsion. But to characterize the ischemic syndrome, CEUS can be used as a safe and accurate method to assess the perfusion parameters of the ovary or the adnexal mass. CEUS can be confidently used in the superacute phase revealing a complete absence of vascularization and in chronic torsion to specify the existence of reduced vascularity in contrast to the contralateral ovary and uterus and to highlight the absence of tumoral vascular distortions.

Additionally, CT can be used to further characterize the ovary if ultrasound findings are ambigous but larger studies need to confirm the diagnostic criteria and guidelines need to be defined (11). MRI may also be useful for the preoperative evaluation of the ovarian viability and thus facilitating prompt surgical intervention (11, 14).

In this case report, the patient had the left ovary affected despite the right-sided predilection and a history of previous pelvic surgery. Symptoms of ovarian torsion are non-specific but the classic presentation includes acute sharp or stabbing pain located unilateral in the lower abdomen, often with nausea and vomiting and even vaginal bleeding, symptoms highy variable depending on the extent of ischemic syndrome (6). Physical examination can reveal abdominal tenderness and a palpable pelvic mass. In some cases with incomplete torsion, patients can experience severe intermittent pain with asymptomatic periods (6). The clinical picture can bring into question other causes of acute abdomen such as ruptured follicular cyst, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, hematosalpinx, appendicitis and diverticulitis (7). In our case, the patient had the classical clinical presentation and in the first instance, the diagnosis was of an ovarian mass leading to torsion.

The diagnosis can be challenging and thus, a comprehensive approach is essential. Imaging studies play an important role for patients with suspected ovarian torsion. The first-line imaging modality in the diagnostic algorithm is pelvic ultrasound and also color Doppler analysis to assess the ovarian blood supply and the degree of vascular compromise (8, 9). Moreover, an emerging modality with vast potential is CEUS, especially when considering the limitation of colour Doppler (10). In the second-line, imaging modalities like computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used when ultrasound findings are nondiagnostic or inconclusive (11). But in order to establish an accurate and definitive diagnosis and to avoid further damage of the ovary, emergency laparoscopy should be performed after a thorough and rapid examination.

Ultrasound is the most important investigation for ovarian torsion and findings may vary but the most constant finding is an unilateral ovarian enlargement (> 4 cm) secondary to impaired venous and lymphatic drainage (12). Other sonographic features include: variable echogenicity, heterogeneous ovarian stroma caused by edema and/or hemorrhage, peripheral cystic structures (“string of pearls” sign) due to the displacement of follicles subsequent to ovarian edema and venous congestion, often a coexistent mass which can be cystic, solid or both and sometimes intraperitoneal free fluid (1, 11, 12). In chronic torsions the ovary has a complex, pseudotumoral appearance with chronic ischemia alternating with hemorrhagic areas. Colour Doppler sonography may be helpful to evaluate the viability of the ovary but the interpretations can be highly variable and some authors dispute its usefulness (11, 13). Traditionally, the presence of blood flow indicates the existence of permeable vessels and thus, that the ovary may still be viable. However, a normal flow cannot rule out ovarian torsion and cannot exclude intermittent torsion. This is consistent with the findings in one study where normal Doppler flow was found in 60% of surgically confirmed cases (9). Sometimes, the classical ”whirlpool” sign (twisted ovarian pedicle) can be observed. Although colour Doppler has some limitations regarding the detection of slow flow and the tissue movement that can simulate the presence of vascular flow, it can still be useful in determing the preoperative viability of the ovary. In our case, ultrasound showed an enlarged ovary, measuring over 4 cm, with a heterogeneously architecture and a moderate amount of intraperitoneal free fluid. Colour Doppler ultrasound demonstrated blood flow of the left ovary and adnexal mass, and thus resulting in a false negative diagnostic of ovarian torsion. But to characterize the ischemic syndrome, CEUS can be used as a safe and accurate method to assess the perfusion parameters of the ovary or the adnexal mass. CEUS can be confidently used in the superacute phase revealing a complete absence of vascularization and in chronic torsion to specify the existence of reduced vascularity in contrast to the contralateral ovary and uterus and to highlight the absence of tumoral vascular distortions.

Additionally, CT can be used to further characterize the ovary if ultrasound findings are ambigous but larger studies need to confirm the diagnostic criteria and guidelines need to be defined (11). MRI may also be useful for the preoperative evaluation of the ovarian viability and thus facilitating prompt surgical intervention (11, 14).

6Teaching points

1. It is impossible to differentiate between ovarian changes secondary to chronic ischemia or an intraovarian tumor mass using transabdominal and/or transvaginal B-mode ultrasound (intrafollicular hemorrhage determines the isoechoic appearance of stromal follicles and thus resulting in a difficult differential diagnosis)

2. MRI is sensitive at detecting blood products however, in this case it failed to detect the degree of major ischemia, which was better demonstrated by CEUS, highlighting the key role of CEUS in the ischemic syndrome.

2. MRI is sensitive at detecting blood products however, in this case it failed to detect the degree of major ischemia, which was better demonstrated by CEUS, highlighting the key role of CEUS in the ischemic syndrome.

7References

1. McWilliams GD, Hill MJ, Dietrich CS. 3rd Gynecologic emergencies. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:265–283.

2. Anteby SO, Schenker JG, Polishuk WZ. The value of laparoscopy in acute pelvic pain. Ann Surg. 1975;181(4):484-486.

3. Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: A fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156–159.

4. Growdon W B, Laufer M R. Ovarian and Fallopian Tube Torsion. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/ovarian-and-fallopian-tube-torsion.

5. Asfour V, Varma R, Menon P. Clinical risk factors for ovarian torsion. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(7):721-725.

6. . Warner MA, Fleischer AC, Edell SL, et al. Uterine adnexal torsion: sonographic findings. Radiology. 1985;154(3):773–775.

7. White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17:231-237.

8. Auslender R; Shen O; Kaufman Y; Goldberg Y; Bardicef M; Lissak A; Lavie O. Doppler and gray-scale sonographic classification of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 34(2):208-11

9. Peña JE; Ufberg D; Cooney N; Denis AL. Usefulness of Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril. 2000; 73(5):1047-50

10. Chaubal, Nitin. Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound in Gynecology. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2015;41:S68.

11. Chang HC, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Radiographics. 2008;28(5):1355-68.

12. Albayram F, Hamper UM. Ovarian and adnexal torsion: spectrum of sonographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2001; 20(10):1083–1089

13. Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:8-12

14. Kimura I, Togashi K, Kawakami S, Takakura K, Mori T, Konishi J. Ovarian torsion: CT and MR imaging appearances. Radiology. 1994;190(2):337-41.

2. Anteby SO, Schenker JG, Polishuk WZ. The value of laparoscopy in acute pelvic pain. Ann Surg. 1975;181(4):484-486.

3. Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: A fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156–159.

4. Growdon W B, Laufer M R. Ovarian and Fallopian Tube Torsion. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/ovarian-and-fallopian-tube-torsion.

5. Asfour V, Varma R, Menon P. Clinical risk factors for ovarian torsion. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(7):721-725.

6. . Warner MA, Fleischer AC, Edell SL, et al. Uterine adnexal torsion: sonographic findings. Radiology. 1985;154(3):773–775.

7. White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17:231-237.

8. Auslender R; Shen O; Kaufman Y; Goldberg Y; Bardicef M; Lissak A; Lavie O. Doppler and gray-scale sonographic classification of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 34(2):208-11

9. Peña JE; Ufberg D; Cooney N; Denis AL. Usefulness of Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril. 2000; 73(5):1047-50

10. Chaubal, Nitin. Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound in Gynecology. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2015;41:S68.

11. Chang HC, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Radiographics. 2008;28(5):1355-68.

12. Albayram F, Hamper UM. Ovarian and adnexal torsion: spectrum of sonographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2001; 20(10):1083–1089

13. Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:8-12

14. Kimura I, Togashi K, Kawakami S, Takakura K, Mori T, Konishi J. Ovarian torsion: CT and MR imaging appearances. Radiology. 1994;190(2):337-41.