- European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology ~ Educating all for competence to practice ultrasound safely

How to Perform CEUS

May 4, 2017

Merkel cell carcinoma [Jun 2017]

June 11, 2017Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon

*Department of Ultrasound, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, 200032 Shanghai, China

**Translational Gastroenterology Unit, Oxford University Hospitals, Oxford, UK

***Med. Klinik 2, Caritas-Krankenhaus Bad Mergentheim, Uhlandstr. 7, 97980 Bad Mer-gentheim.

A 24 year old woman complained of recurrent lower abdominal pain for 6 months. She was referred for colonoscopy. There was no palpable mass on digital rectal examination. Blood chemistry, full blood count, coagulation profile, al-fa-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen were within normal limits.

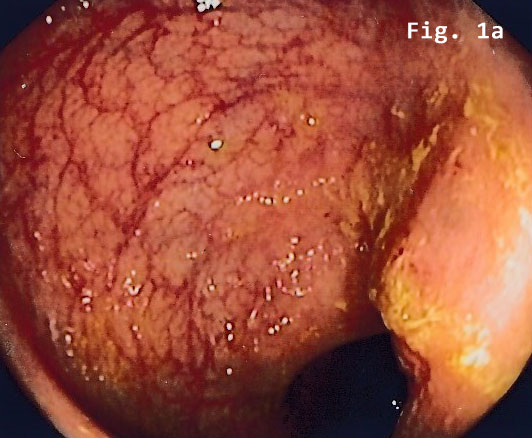

Colonoscopy revealed a semi-circular polypoid lesion in the sigmoid colon suggesting malig-nancy [Figure 1].

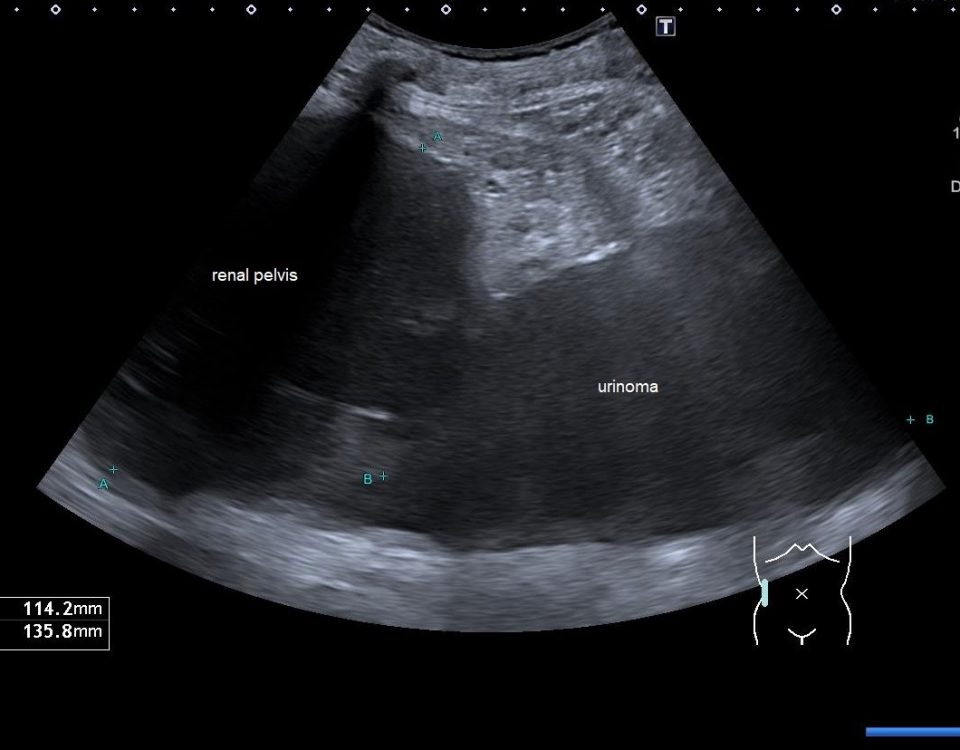

Transabdominal B-mode ultrasound (BMUS) confirmed a 40 mm sized heterogeneous hy-poechoic lesion infiltrating the sigmoid colon [Figure 2].

Contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) showed a rapidly and heterogeneously enhancing lesion during the arterial and venous phases [Figure 3]. Contrast enhanced colour Doppler ultra-sound confirmed the finding.

Endorectal endoscopic ultrasound of the sigmoid colon revealed transmural extension of the mass and confirmed the transcutaneous finding. The lesion was well vascularized [Figure 2].

Subsequently, the patient underwent laparoscopic sigmoid resection. Microscopic examina-tion disclosed endometrial stroma and gland islands located between muscular fibres, subse-rosa and serosa. The pathology result was reported as extragenital endometriosis. The post-operative period was uneventful.

Clinically, intestinal endometriosis is rare and may present a major diagnostic challenge. Here we report a case of transmural endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon and present the findings in endoscopy, ultrasound, CEUS and endoscopic ultrasound.

The first laparoscopic approach to intestinal endometriosis has been reported in 1980 [(6)]. The assumed pathomechanism for extragenital endometriosis is retrograde spread as pro-posed by Sampson, which refers to propagation of endometrial cells into the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes during menstruation followed by dissemination to other areas [(7)].

A prospective study performed by Roman et al. [(11)] demonstrated that women presenting with rectal endometriosis were more likely to present various digestive complaints such as cyclic defecation pain and cyclic constipation. If left untreated, progressive endometriosis may result in partial or complete bowel obstruction requiring surgical resection [(12)].

The degree of symptoms may not correlate to the size of the lesions and painful symptoms are not indicative of surgical intervention. Some patients with extensive endometriosis affect-ing the rectosigmoid can be almost asymptomatic [(5)], while others with small lesions can present with severe symptoms. This makes it more difficult to determine the need for inter-vention, especially radical surgery. Evaluating only patients with endometriosis in the rec-tosigmoid, 48% and 84% had also ovarian endometriosis and retrocervical lesions, respective-ly [(13)].

The majority of patients with intestinal endometriosis are diagnosed at laparoscopy or lapa-rotomy. Diagnosing intestinal endometriosis in the bowel wall involving the serosa, muscularis propria and submucosa is usually straightforward in resected bowel specimen [(15)].

In a literature review, Meuleman et al. [(17)] reported that 95% of patients undergoing bowel resection had bowel serosa involvement; 95% had lesions infiltrating the muscularis while 38% had lesions infiltrating the submucosa and 6% had lesions infiltrating the mucosa.

Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and colonoscopy can be helpful in localising the pathology. Meuleman et al. [(17)] described that in 59% of the studies analyzed, the pre-operative assessment of bowel endometriosis included barium ene-ma (26%), CT (31%) and/or MRI (28%). Advances in imaging technology and adequate training in image analysis have made it possible to identify characteristics of endometriosis nodules pre-operatively [(1)]. The detailed imaging findings allow us to define and plan the optimal surgical procedure. This permits proper patient counselling and consenting. It facilitates ap-propriate selection of a multidisciplinary surgical team aiming at the best patient outcome [(22)].

Ultrasound characteristics for bowel endometriosis, including transabdominal, transrectal, and transvaginal approaches have been described [(23)]. Diagnostic criteria include a hy-poechoic, irregular-shaped area corresponding to a layer of hypertrophic muscularis propria surrounded by a hyperechoic rim including mucosa, submucosa, and serosa [(24)].

When endometriosis involves the recto-sigmoid, transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) with bowel preparation is able to define not only the size and number of lesions, but also the depth of invasion into the bowel wall and the distance from the anal verge [(13, 25)].

At MRI, a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 99% has been reported in 60 patients with intes-tinal involvement [(26)].

Although most patients respond to medical treatment, the recurrence rate is very high after cessation of therapy. Therefore, surgery should be considered first choice treatment, especial-ly in young patients and those with severe symptoms. The recurrence rate after total excision is very low. Surgical treatment provides excellent results, with > 85% of women showing com-plete improvement of symptoms and recurrence rates lower than 5% [(29)].

The completeness of surgical excision seems to determine the rate of recurrence [(31, 32)],. This was shown when clinical and histological characteristics were examined as possible pre-dictive factors for bowel endometriosis recurrence after laparoscopic segmental bowel resec-tion. Three independent predictor factors, positive bowel resection margins, age < 31 years and body mass index ≥ 23 kg/m2, were also significantly associated with recurrence which was observed in 16% of all patients. The complete excision of bowel endometriosis appears most effective for avoiding recurrence of the disease.

- Sheffield LJ, Halliday JL, Jensen F. Maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder's syndrome) and chondrodysplasia punctata. J Med Genet. 1991;28(7):503-4.

- Olow-Nordenram M, Valentin J. An etiologic study of maxillonasal dysplasia--Binder's syndrome. Scand J Dent Res. 1988;96(1):69-74.

- Levaillant JM, Moeglin D, Zouiten K, Bucourt M, Burglen L, Soupre V, et al. Binder phenotype: clinical and etiological heterogeneity of the so-called Binder maxillonasal dysplasia in prenatally diagnosed cases, and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(2):140-50.

- Alessandri JL, Ramful D, Cuillier F. Binder phenotype and brachytelephalangic chondrodysplasia punctata secondary to maternal vitamin K deficiency. Clin Dysmorphol. 2010;19(2):85-7.

- Howe AM, Lipson AH, Sheffield LJ, Haan EA, Halliday JL, Jenson F, et al. Prenatal exposure to phenytoin, facial development, and a possible role for vitamin K. Am J Med Genet. 1995;58(3):238-44.

- Cook K, Prefumo F, Presti F, Homfray T, Campbell S. The prenatal diagnosis of Binder syndrome before 24 weeks of gestation: case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(6):578-81.

- Blumenfeld YJ, Davis AS, Hintz SR, Milan K, Messner AH, Barth RA, et al. Prenatally Diagnosed Cases of Binder Phenotype Complicated by Respiratory Distress in the Immediate Postnatal Period. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(6):1353-8.

- Boulet S, Dieterich K, Althuser M, Nugues F, Durand C, Charra C, et al. Brachytelephalangic chondrodysplasia punctata: prenatal diagnosis and postnatal outcome. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;28(3):186-90.

- Cantarell SM, Azuara LS, Perez SP, Juanos JL, Navarro FM, Martinez MC. Prenatal diagnosis of Binder's syndrome: report of two cases. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2016;43(2):279-83.

- Cuillier F, Cartault F, Lemaire P, Alessandri JL. Maxillo-nasal dysplasia (binder syndrome): antenatal discovery and implications. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2005;20(4):301-5.

- Monasterio FO, Molina F, McClintock JS. Nasal correction in Binder's syndrome: the evolution of a treatment plan. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(5):299-308.

Medizinische Klinik 2

Caritas-Krankenhaus

Uhlandstr. 7

97980 Bad Mergentheim

Tel:+49 7931 58 2201

Email: christoph.dietrich@ckbm.de

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig1b.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig2a.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig2b.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig2c.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig3a.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig3b.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig3c.jpg)

![Endometriosis infiltrating the sigmoid colon</br> [May 2017]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_may2017_fig4.jpg)