- European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology ~ Educating all for competence to practice ultrasound safely

CEUS Non Liver

April 28, 2016

Schwannoma and jugular vein thrombosis diagnosed by using modern imaging technology [Jun 2016]

June 11, 2016Ultrasound diagnosis of uncomplicated interstitial pregnancy

Department of Radiology and Imaging, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicolae Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova.

Email: puiusv@yahoo.com

Despite technical advances in recent years, accurate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy (EP) is often difficult to achieve and misdiagnosis remains common. While tubal pregnancies are the most common, an increase in ectopics of unusual location is being observed, particularly after assisted reproduction techniques. An interstitial pregnancy (IP) is a rare and dangerous variant of an EP, diagnosis being often difficult to establish in early stages. The purpose of this review is to summarize the sonographic criteria for the diagnosis of interstitial pregnancies, based on two case studies.

Case one

A 37-year-old woman presented for a routine dating scan at 6 weeks amenorrhea. On appointment she was asymptomatic. Transvaginal sonography revealed an empty uterine cavity and a small gestational sac with a yolk sac located eccentrically outside the endometrium, at least 5 mm from the lateral edge of the uterine cavity (Fig. 1a). A thin myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac and an echogenic line (interstitial line) extending from endometrium to the ectopic sac was clearly seen (Fig.2b). An interstitial pregnancy was presumed. Laparotomy with excision of the interstitial pregnancy was performed. The postoperative period was uncomplicated.

Case two

A 39-year-old woman presented for a routine dating scan at 8 weeks 6 days amenorrhea. At examination she also was asymptomatic. Ultrasound examination revealed an empty uterine cavity with a regular endometrium and a gestational sac with a viable embryo located in the interstitial portion of the right fallopian tubes, separate and greater than 1 cm from the lateral edge of the uterine cavity (Fig.2a). The sac was surrounded by a thin myometrial mantle (Fig.2b). Color Doppler sonography revealed peritrophoblastic blood flow around the gestational sac and heart movements (Video 1). No fluid was seen in the pouch of Douglas. Bulging of the outer contour of the uterus in the cornual region was shown on 3D ultrasound (Fig.2c). Laparotomy with excision of the interstitial portion of fallopian tube and right cornual part of the uterus was performed. The postoperative period was uncomplicated.

Despite technical advances in recent years, accurate diagnosis of interstitial ectopic pregnancy is often difficult to achieve and misdiagnosis remains common [5,6]. Interstitial pregnancy is suspected when a regular endometrium without visible gestational sac and the gestational sac or mass located eccentrically outside the endometrium and surrounded by myometrium is seen [7,8]. On conventional ultrasound examination (2D) common findings include:

1. Interstitial line sign; describes an echogenic line (interstitial portion of the fallopian tube) that extends from endometrium to the ectopic sac or mass, but not surrounding them. Has reported sensitivity (SE) of 80% and specificity (SP) of 99% for IP diagnosing [9].

2. Eccentric position of the gestational sac separate from the uterine cavity (40% SE and 62% SP), greater than 1 cm away from the lateral wall of the uterine cavity [10].

3. A thin (less than 5 mm) or even absent myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac or echogenic mass (40% SE and 74 % SP) [11].

Timor-Tritsch et al. [10] suggested that interstitial ectopics might be diagnosed when: the uterine cavity is empty, a gestational sac located at least 1 cm from the lateral edge of the uterine cavity and a thin myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac. Hafner et al. [12] found that the interstitial segment of the tube often measure less than 1 cm in length. Therefore, a strict application of a 1 cm cut-off may lead to an interstitial pregnancy being misdiagnosed as intrauterine pregnancy.

Jurkovic and Mavrelos [13] have proposed a combination of two findings as being diagnostic for interstitial pregnancy: visualization of the interstitial line between the gestational sac and the lateral edge of the endometrial cavity and the myometrial mantle around the ectopic sac.

3D ultrasound facilitates the visualization of the interstitial portion of the tube, due to its capability to image the coronal plane of the uterus and may be helpful in differentiating between intrauterine and interstitial pregnancies in difficult cases [14].

Clinical symptoms depend on the gestational age. An IP develops much longer before becoming symptomatic. Surrounding myometrium, which is a thicker and more distensible, frequently allows the pregnancy to progress into the second trimester. Uterine rupture most commonly occurs late in the first trimester or early in the second trimester. Therefore, interstitial pregnancies often are found ruptured at the time of diagnosis [4]. Given highly vascularized environment and close proximity to the uterine artery, rupture can often result in severe life-threatening hemorrhage. Delayed diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy can lead to high maternal mortality rate, much higher than in the case of tubal ectopic pregnancies: 2-2,5% versus 0,14% [15].

Depending on the gestational age, different treatment options are available for interstitial pregnancy. Surgical management usually involves cornual resection (laparoscopic or laparotomic) or hysterectomy. Conservative management presumes systemic or local application (ultrasound-guided injection into the GS) of methotrexate. In cases of heterotopic interstitial pregnancy, potassium chloride administration exclusively to the ectopic gestational sac can be used. Sometimes expectant management with close monitoring for falling β-hCG levels and shrinking gestational mass is used. The follow-up period for expectantly managed cases can be very long, a gestational mass can persist for many weeks, even months [16].

2. Honemeyer U, Plavsic SK, Kurjak A. Interstitial ectopic pregnancy: the essential role of ultrasound diagnosis. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 4:321–325.

3. Tulandi T, Al-Jaroudi D. Interstitial pregnancy: results generated from the Society of Reproductive Surgeons Registry. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103(1): 47–50.

4. Kurjak A, Kupesic S. Color Doppler and 3D Ultrasound in Gynecology, Infertility and Obstetrics. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Publishers; 2003.

5. Chan LY et al: Pitfalls in diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 82 (9): 867-70, 2003.

6. Malinowski A, Bates SK. Semantics and pitfalls in the diagnosis of cornual/ interstitial pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2006; 86:1764.e11–1764.e14.

7. D. V. Valsky and S. Yagel. Ectopic pregnancies of unusual location: management dilemmas. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008; 31: 245–251

8. Lee GS et al: Diagnosis of early intramural ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 33(4):190-2, 2005

9. Ackerman TE, Levi CS, Dashefsky SM, Holt SC, Lindsay DJ. Interstitial line: sonographic finding in interstitial (cornual) ectopic pregnancy. Radiology 1993; 189(1): 83 –87.

10. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Matera C, Veit CR. Sonographic evolution of cornual pregnancies treated without surgery. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 1044–1049.

11. Resa E. Lewiss, MD, Nadia M. Shaukat, MD, Turandot Saul, MD, RDMS. The Endomyometrial Thickness Measurement for Abnormal Implantation Evaluation by Pelvic Sonography. J Ultrasound Med 2014; 33:1143–1146

12. Hafner T, Aslam N, Ross JA, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. The effectiveness of non-surgical management of early interstitial pregnancy: a report of ten cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 13: 131–136.

13. D. Jurkovic and D. Mavrelos. Catch me if you scan: ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30: 1–7.

14. Izquierdo LA, Nicholas MC. Three-dimensional Transvaginal sonography of interstitial pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound 2003; 31(9): 484–487.

15. Moawad NS, Mahajan ST, Moniz MH, Taylor SE, Hurd WW. Current diagnosis and treatment of interstitial pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202:15–29.

16. Jermy K, Thomas J, Doo A, Bourne T. The conservative management of interstitial pregnancy. BJOG 2004; 111: 1283–8.

Figure 1a. Transvaginal ultrasound scan, transverse view. Empty uterine cavity. A small gestational sac with a yolk sac located outside from the lateral edge of the uterine cavity.

Figure 1b. Transvaginal ultrasound scan (transverse view). Note a thin myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac and an interstitial line (arrow), extending from endometrium to the ectopic sac.

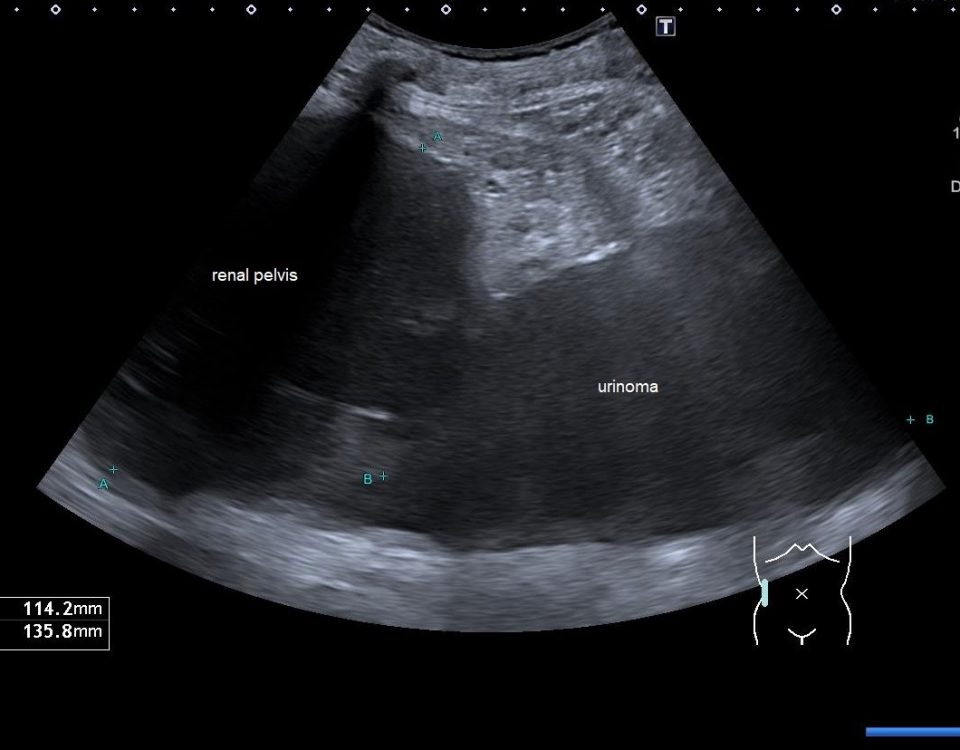

Figure 2a. Abdominal ultrasound (transverse view). Empty uterine cavity with a regular endometrium and a gestational sac located in the right interstitial area of the uterus.

Figure 2b. A gestational sac with one live embryo (CRL measuring 2.20 cm, corresponding to 8 weeks 6 days amenorrhea) located in right interstitial area.

Figure 2c. 3D ultrasound (coronal view). Eccentrically located gestational sac outside the endometrium and surrounded by myometrium. Bulging of the outer contour of the uterus in the cornual region.

Video 1. Peritrophoblastic blood flow around the interstitial gestational sac and heart movements on Color Doppler.

![Ultrasound diagnosis of uncomplicated interstitial pregnancy</br> [May 2016]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm-may2016_fig1b.jpg)

![Ultrasound diagnosis of uncomplicated interstitial pregnancy</br> [May 2016]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm-may2016_fig2a.jpg)

![Ultrasound diagnosis of uncomplicated interstitial pregnancy</br> [May 2016]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm-may2016_fig2b.jpg)

![Ultrasound diagnosis of uncomplicated interstitial pregnancy</br> [May 2016]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm-may2016_fig2c.jpg)