The clue is in the bubbles [Jul 2019]

July 24, 2019

One dip too far: an unusual cause of exercise induced chest pain [Sep 2019]

September 24, 2019Non Hodgkin lymphoma of the small intestine

AUTHORS:

Dr. Ruth Thees-Laurenz

Center of Radiology, Neuroradiology, Ultrasound and Nuclear medicine

Interdisciplinary Sonography Center, Brüderkrankenhaus Trier, Nordallee 1, D-54296 Trier

Mail: R.Thees-Laurenz@bk-trier.de

Dr. Ruth Thees-Laurenz

Center of Radiology, Neuroradiology, Ultrasound and Nuclear medicine

Interdisciplinary Sonography Center, Brüderkrankenhaus Trier, Nordallee 1, D-54296 Trier

Mail: R.Thees-Laurenz@bk-trier.de

Video 1: Lymphoma in the ileum, transverse scan

Video 2: Perfusion of the lymphoma

1Clinical History

A 75 year old male patient was admitted with recurrent chest pain and anaemia. He had a history of recurrent lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding caused by caecal angiodysplasia. At admission, there were no signs of bleeding, no abdominal pain, no change in bowel habits, nor weight loss.

Clinical examination showed a slight tenderness in the lower abdomen.

An ultrasound examination of the abdomen was performed using a Philips Epiq 7 system with convex and linear transducers.

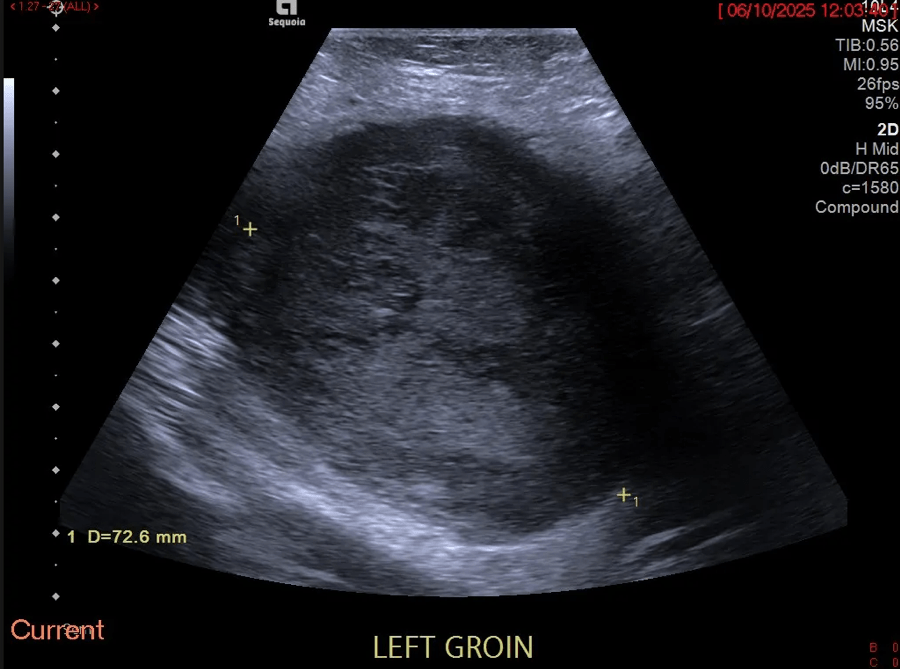

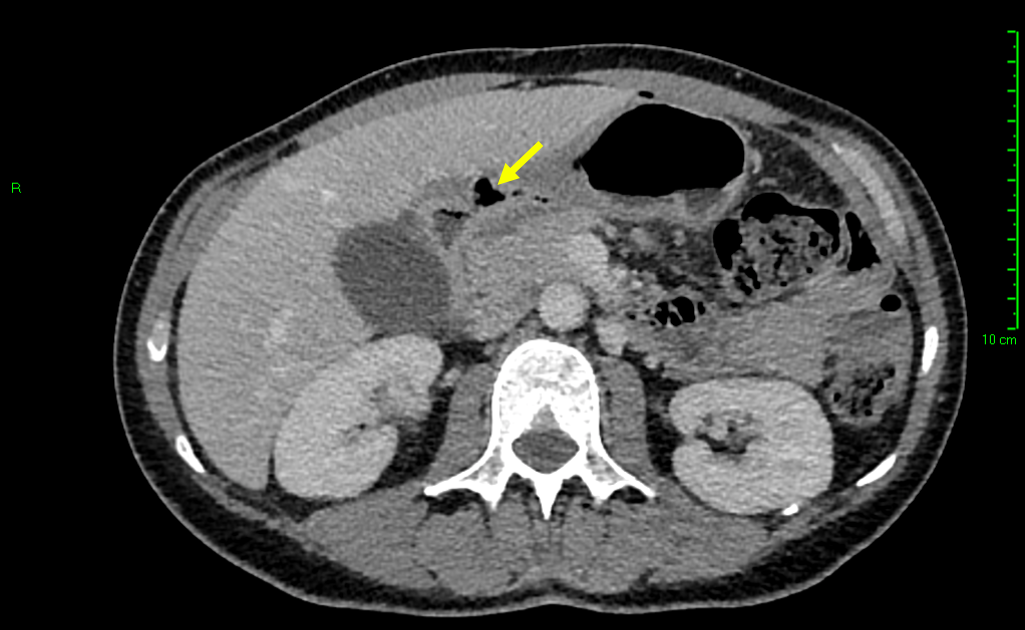

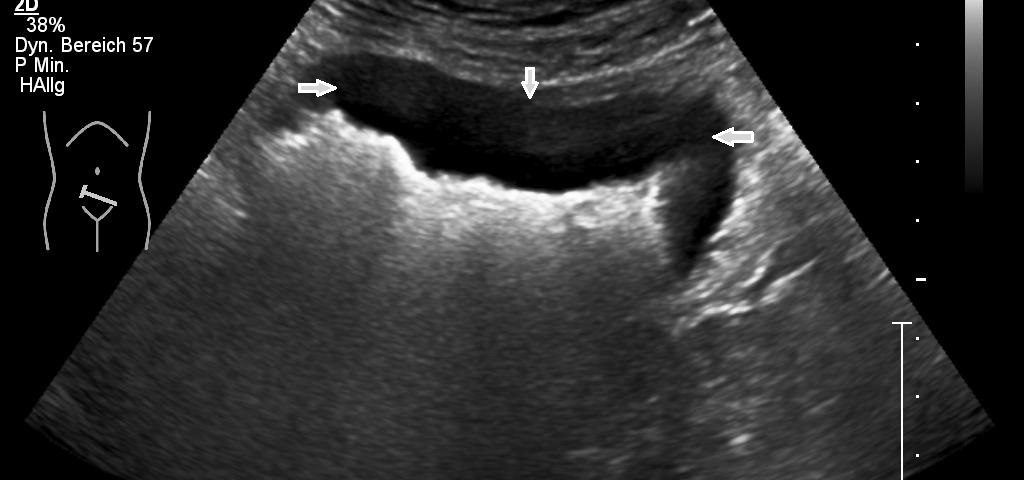

The examination revealed a segment of the ileum with substantial semicircular and homogenous hypoechoic wall thickening over a length of about 10 cm. There was no differentiation of wall layers possible. There was also no intraluminal narrowing of the thick- walled bowel segment or bowel dilatation. Colour Doppler revealed straight vessels within the hypoechoic thickened wall.

Sonography also revealed enlarged hypoechoic aortocaval and mesenteric lymph nodes. These lymph nodes showed a homogenous and hypoechoic parenchyma, with no echogenic hilar structures visible. These nodes measured up to 3.8 cm in maximal diameter, the short axis of the greatest lymph node was 2,4cm and the cortical thickness 2cm.

The patient developed a perforation of the Ileum with generalised peritonitis. He underwent surgical treatment with partial resection of the ileum and ileostomy. Histopathologic report revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). After completion of the diagnostic investigations, an Ann arbor state IIIa was confirmed.

Clinical examination showed a slight tenderness in the lower abdomen.

An ultrasound examination of the abdomen was performed using a Philips Epiq 7 system with convex and linear transducers.

The examination revealed a segment of the ileum with substantial semicircular and homogenous hypoechoic wall thickening over a length of about 10 cm. There was no differentiation of wall layers possible. There was also no intraluminal narrowing of the thick- walled bowel segment or bowel dilatation. Colour Doppler revealed straight vessels within the hypoechoic thickened wall.

Sonography also revealed enlarged hypoechoic aortocaval and mesenteric lymph nodes. These lymph nodes showed a homogenous and hypoechoic parenchyma, with no echogenic hilar structures visible. These nodes measured up to 3.8 cm in maximal diameter, the short axis of the greatest lymph node was 2,4cm and the cortical thickness 2cm.

The patient developed a perforation of the Ileum with generalised peritonitis. He underwent surgical treatment with partial resection of the ileum and ileostomy. Histopathologic report revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). After completion of the diagnostic investigations, an Ann arbor state IIIa was confirmed.

2Discussion

Extranodal lymphoma manifestation occurs in about 40% of patients with lymphoma and has been described in virtually every organ and tissue.

Lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract is the most common abdominal manifestation after the infiltration of the spleen and the liver [1,2,3]. Transabdominal ultrasonography has a high sensitivity for detection of pathological lymph nodes, it is also useful in the detection of GIT involvement in extra nodal lymphoma [1,4,5].

Extranodal disease is more common in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma than in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It may be part of a systemic lymphoma or could be the first presentation. Lymphoma is the most common malignancy of the small bowel. In HIV-positive patients due to the B-cell hyperactivation the incidence in some countries has increased [3,6].

The lamina propria and the submucosa of the bowel wall contain lymphoid elements, so lymphomatous change originates within these layers.

Ultrasonographic signs of bowel lymphoma are variable. Circumferential wall thickening is the most common pattern on sonography where a common described feature is of a thickened hypoechoic to anechoic wall with an echogenic centre and is described as a the “target-sign” [7,8]

A classic target pattern with no detectable wall layers is characteristic of advanced circumferential intestinal infiltration. Aneurysmal dilatation of the involved bowel may be seen, caused by an infiltration of the muscularis propria and destruction of the autonomic nerve plexus by the tumour. Lymphoma rarely results in bowel obstruction because the tumour does not elicit a desmoplastic response. Lymphoma infiltration sometimes is confined to the mucosa where only transmural involvement forms part of the circumference of the bowel wall [1,7,8].

Other findings are nodular or bulky tumour spread caused by extraluminal involvement. Complications of lymphomas involving the GI-tract are obstruction, perforation, fistula or bleeding [2,5,7].

The differential diagnosis of the changes in the thickened bowel wall include benign and malignant diseases. Benign changes include segmental bowel inflammation due to Crohn’s disease,,colitis, diverticulitis, tuberculosis, ischaemia and also haematoma in the bowel wall [8].

Although malignant gastrointestinal tumors can give a similar appearance, patients with a thickened bowel wall caused by inflammation mostly show bowel wall thickening with associated signs of inflammation. In particular, there is hyperechoic, thickened mesenteric fatty tissue and/or free fluid.

Extranodal disease is more common in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma than in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It may be part of a systemic lymphoma or could be the first presentation. Lymphoma is the most common malignancy of the small bowel. In HIV-positive patients due to the B-cell hyperactivation the incidence in some countries has increased [3,6].

The lamina propria and the submucosa of the bowel wall contain lymphoid elements, so lymphomatous change originates within these layers.

Ultrasonographic signs of bowel lymphoma are variable. Circumferential wall thickening is the most common pattern on sonography where a common described feature is of a thickened hypoechoic to anechoic wall with an echogenic centre and is described as a the “target-sign” [7,8]

A classic target pattern with no detectable wall layers is characteristic of advanced circumferential intestinal infiltration. Aneurysmal dilatation of the involved bowel may be seen, caused by an infiltration of the muscularis propria and destruction of the autonomic nerve plexus by the tumour. Lymphoma rarely results in bowel obstruction because the tumour does not elicit a desmoplastic response. Lymphoma infiltration sometimes is confined to the mucosa where only transmural involvement forms part of the circumference of the bowel wall [1,7,8].

Other findings are nodular or bulky tumour spread caused by extraluminal involvement. Complications of lymphomas involving the GI-tract are obstruction, perforation, fistula or bleeding [2,5,7].

The differential diagnosis of the changes in the thickened bowel wall include benign and malignant diseases. Benign changes include segmental bowel inflammation due to Crohn’s disease,,colitis, diverticulitis, tuberculosis, ischaemia and also haematoma in the bowel wall [8].

Although malignant gastrointestinal tumors can give a similar appearance, patients with a thickened bowel wall caused by inflammation mostly show bowel wall thickening with associated signs of inflammation. In particular, there is hyperechoic, thickened mesenteric fatty tissue and/or free fluid.

3Teaching Points

Typical aspects and features of intestinal lymphoma are illustrated.

4References

1. Goerg C, Schwerk WB; Goerg K: Sonography of gastrointestinal lymphoma; AJR 1990; 155: 795-798

2. Vaidya R et al: Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: incidence and clinical features; Annals of Oncology 2013; 24: 2439–2443

3. Yin L, Chen CQ, Peng CH et al. Primary Small-bowel Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: a Study of Clinical Features, Pathology, Management and Prognosis¸ The Journal of International Medical Research 2007; 35: 406 – 415

4. Atkinson NSS ; Bryant RV, Dong Y: How to perform gastrointestinal ultrasound. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 6931-6941

5. Hasaballah M, Abdel-Malek R, Zakaria Z, Marie MS, Naguib MS. Transabdominal ultrasonographic features in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2018;9 :1190-1197.

6. Lo Re Giuseppe et al: Radiological Features of Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Gastroenterology Research and Practice; Volume 2016, Article ID 2498143

7. Ahn SE , Moon SK, Lee DH: Sonography of Gastrointestinal Tract Diseases; J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35:1543–1571

8. Muradali D, Goldberg D: US of Gastrointestinal Tract Disease. RadioGraphics 2015; 35:50–70

2. Vaidya R et al: Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: incidence and clinical features; Annals of Oncology 2013; 24: 2439–2443

3. Yin L, Chen CQ, Peng CH et al. Primary Small-bowel Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: a Study of Clinical Features, Pathology, Management and Prognosis¸ The Journal of International Medical Research 2007; 35: 406 – 415

4. Atkinson NSS ; Bryant RV, Dong Y: How to perform gastrointestinal ultrasound. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 6931-6941

5. Hasaballah M, Abdel-Malek R, Zakaria Z, Marie MS, Naguib MS. Transabdominal ultrasonographic features in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2018;9 :1190-1197.

6. Lo Re Giuseppe et al: Radiological Features of Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Gastroenterology Research and Practice; Volume 2016, Article ID 2498143

7. Ahn SE , Moon SK, Lee DH: Sonography of Gastrointestinal Tract Diseases; J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35:1543–1571

8. Muradali D, Goldberg D: US of Gastrointestinal Tract Disease. RadioGraphics 2015; 35:50–70

![Non Hodgkin lymphoma of the small intestine </br> [Aug 2019]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Aug2019-Fig.-1-a-with-arrows.jpg)

![Non Hodgkin lymphoma of the small intestine </br> [Aug 2019]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/aug2019-Fig.-1-b-with-arrows.jpg)

![Non Hodgkin lymphoma of the small intestine </br> [Aug 2019]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Aug2019-05_Fig.-2.jpg)

![Non Hodgkin lymphoma of the small intestine </br> [Aug 2019]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Aug2019-02_Fig-3.jpg)