Diagnosing Thoracic Aortic Dissection using Bedside Ultrasound in an Emergency Department in a Norwegian University Teaching Hospital [September 2021]

September 6, 2021

Non-inflamed Stump Appendix within the Cecum [November 2021]

November 1, 2021The role of ultrasound in detection and characterisation of incidental Renal Cell Carcinomas

AUTHOR

Eva Gudiksen, Department of radiology, Esbjerg, University hospital of Southern Denmark

Eva Gudiksen, Department of radiology, Esbjerg, University hospital of Southern Denmark

1Clinical History

54-year-old male. Ultrasound of the upper abdomen requested by GP.

Information on request form:

“Five days of strong RUQ pain. No fever. Pain exacerbates when moving. No coughing, dyspnoea or purulent sputum. No DVT. Lung stethoscopy normal. Severe pain below right curvature. Soft abdomen. Normal bowel habits, no blood or change of colour in stools. No weight loss. No other dyspepsia. Denies alcohol abuse. Normal ECG. Urine test normal.

Request for ultrasound of upper abdomen with special concern regards liver/biliary system, pancreas and right kidney.”

Information on request form:

“Five days of strong RUQ pain. No fever. Pain exacerbates when moving. No coughing, dyspnoea or purulent sputum. No DVT. Lung stethoscopy normal. Severe pain below right curvature. Soft abdomen. Normal bowel habits, no blood or change of colour in stools. No weight loss. No other dyspepsia. Denies alcohol abuse. Normal ECG. Urine test normal.

Request for ultrasound of upper abdomen with special concern regards liver/biliary system, pancreas and right kidney.”

2Image findings

According to local protocol, if the request question isn’t specific or for evaluation of a known pathology, a full abdominal study is performed.

As the patient is in the lower end of normal BMI, a probe frequency of 6 MHz was selected to obtain optimum resolution with the highest possible frequency.

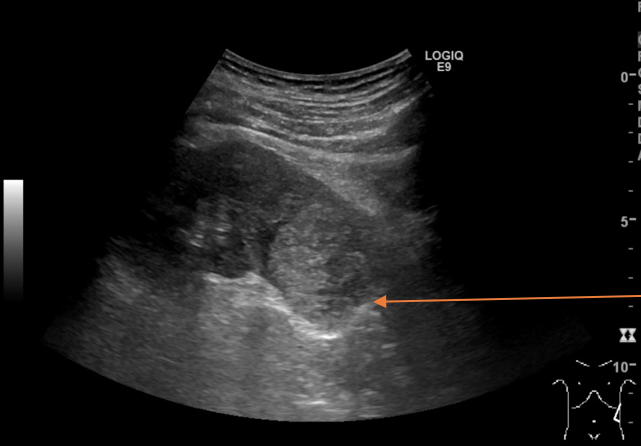

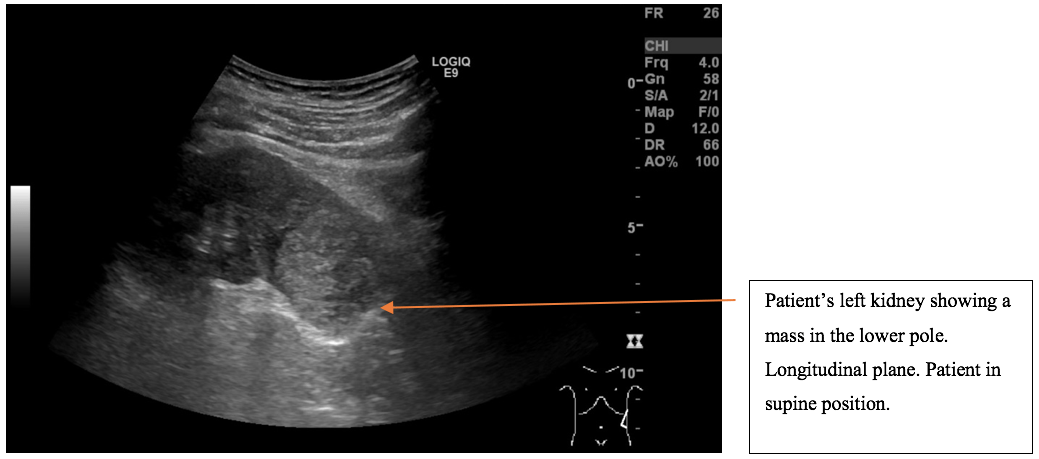

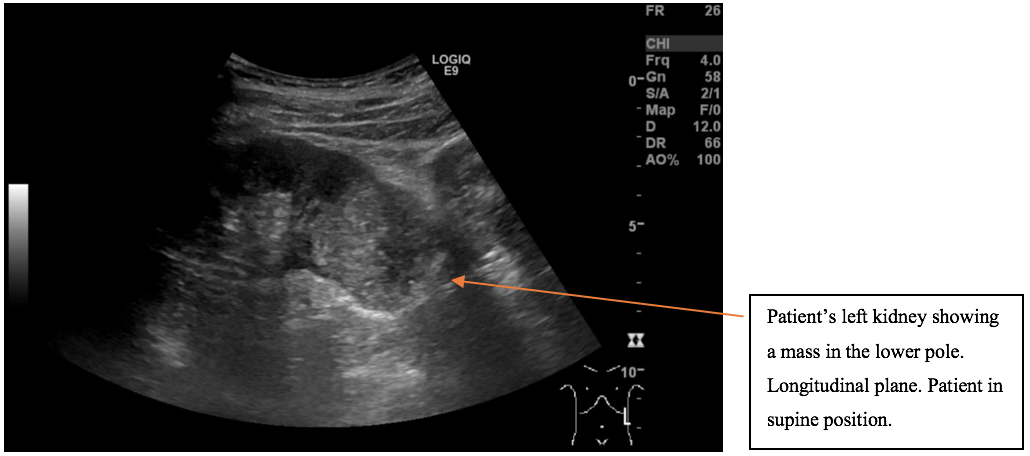

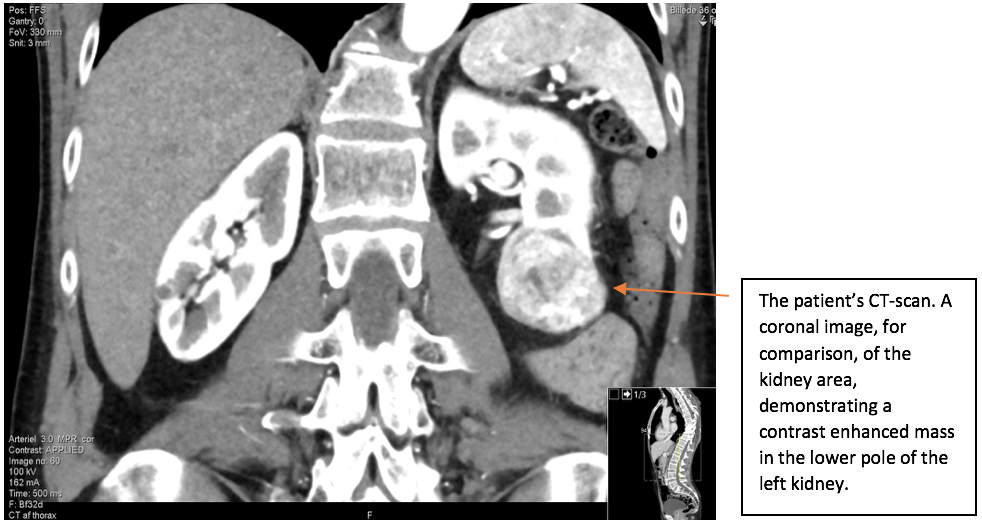

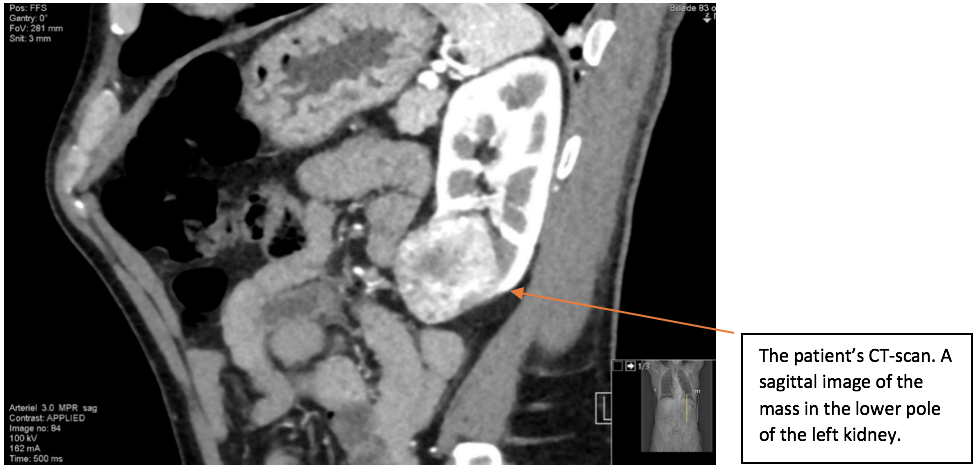

A mass was found in the lower pole of the left kidney. The left kidney including the renal mass is fully examined in both longitudinal and transverse axis in supine and in the right side down, posterior oblique position. The mass in the lower pole measured 5 cm and was a solid, well-defined focal lesion with heterogenous echotexture. The patient was sent directly to the urology unit and a multi phasic contrast-enhanced CT-scan of thorax/abdomen is performed. The tumour of the left kidney was reported as most possible malignant with appearance of a renal cell carcinoma with no signs of metastases.

As the patient is in the lower end of normal BMI, a probe frequency of 6 MHz was selected to obtain optimum resolution with the highest possible frequency.

A mass was found in the lower pole of the left kidney. The left kidney including the renal mass is fully examined in both longitudinal and transverse axis in supine and in the right side down, posterior oblique position. The mass in the lower pole measured 5 cm and was a solid, well-defined focal lesion with heterogenous echotexture. The patient was sent directly to the urology unit and a multi phasic contrast-enhanced CT-scan of thorax/abdomen is performed. The tumour of the left kidney was reported as most possible malignant with appearance of a renal cell carcinoma with no signs of metastases.

3Images

The scan showing are a selection of the images obtained during both the ultrasound and the subsequent CT scan. Ultrasound images are demonstrated in the longitudinal plane only, owing to the poor visualisation of the mass in sagittal plane. However, the CT scan demonstrates the mass in multiple planes.

4Diagnosis

Renal Cell Carcinoma

5Sonographic appearance of RCC and the role of Ultrasound in diagnosis and interpretation of RCC

Most RCC appear solid on ultrasound and can be hypoechoic (10%), isoechoic (86%) or hyperechoic (4%). Smaller lesions less than 3 cm are often echogenic compared with surrounding renal parenchyma. Therefore, small lesions can have a similar appearance as an angiomyolipoma (AML) and it can be difficult to differentiate the two entities. AMLs often appear with a weak posterior shadowing. Some RCCs have a hypoechoic rim and/or small, intralesional cystic spaces, which are not seen with AMLs (Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al., 2011). However, a recent study from 2016 suggests that small (<1-cm) echogenic renal masses are always AML or another benign entity (Sidhar, K. and McGahan, J.P. et al.,2016).

Tumours larger than 3 cm, as in this case, are most often either isoechoic (49%) or mildly hyperechoic (33%), with only 4% found to be very hyperechoic (Sidhar, K. and McGahan, J.P. et al.,2016).

Macroscopic calcification may be seen in 8-18% of RCCs. Central calcification is seen in 87% of all malignant tumours (Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al., 2011). The use of doppler in RCC ultrasound may detect high tumour vascularity, however the absence of high frequency doppler shift does not exclude malignancy (Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al., 2011).

Compared to CT and MRI, ultrasound is a simple and safe examination, very cost effective, non-invasive, and contrary to CT gives no ionising radiation exposure to patients (Moloney, F. and Murphy, K.P et al., 2014 + O’Neill, W.C., 2014). However, ultrasound has limitations such as being less sensitive in detecting small renal masses < 3 cm (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010) as well as being highly operator dependent and sensitive to bowel gas and patient’s body habitus (Lema, P.C and Kim, J.H et al., 2017). The latter reference refers to an article in the Journal of vascular diagnostics and interventions about pitfalls and limitations when scanning the abdominal aorta. However, the limitations, such as bowel gas, operator dependence etc. are typical for ultrasound in general.

In the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma, updated in 2019, MRI and CEUS are both recommended to evaluate unclear cystic lesions, especially Bosniak III cysts, as MRI and CEUS in these cases show higher sensitivity and specificity than CT (Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al., 2019). Hence, ultrasound can be useful in characterizing whether a lesion is likely to be cystic and benign e.g. a hyperdense cyst is found on a non-contrast CT. It could also be utilised in cases where iodinated contrast media is contraindicated, as the most important criteria for differentiating malignancy in solid renal masses, according to the above urology guidelines, is the presence of contrast enhancement or restriction of fluid on MRI diffusion weighted imaging (Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al., 2019).

Although ultrasound plays a great role in incidental findings of RCC during routine abdominal examinations (Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al., 2018 + Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017) and in differentiating between solid and cystic renal masses as well as CEUS being helpful in specific cases providing information about vascularity, ultrasound imaging has limitations in further characterisation of solid tumours as well as staging of malignancy (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010).

Leveridge et al. refers to a study which claims that CEUS can be employed in staging of RCC, with CT and ultrasound being almost equivalent for predicting the T-stage (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010).

The stage of RCC is usually reported using the tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification. This is based on the extent of the primary tumour (T), whether lymph nodes are affected (N) and whether metastases are present (M) (Knipe, H and Maller, V. et al., 2018). Therefore, even if CEUS is useful for predicting T-stage, the M and N stage will still need to be predicted. This leaves the use of CEUS for full staging inadequate.

In evaluation of renal masses, the main goals are to detect and classify the lesion (Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017). The primary criterion for diagnosing RCC is the identification of contrast enhancement and assessment of the tumour vascularity which can be used in suggesting a specific subtype of RCC. For a potential surgical and/or ablation intervention, accurate tumour staging, and information about renal vascular anatomy must be obtained (Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017).

There is a wide agreement that CT is the first line modality for staging of locoregional and suspected metastatic disease (Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al., 2018 + Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017 + Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al., 2018). Later on, the pattern of contrast enhancement of the tumour on CT can be used as a good indicator of treatment success (Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al., 2018). Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to use CEUS for T-staging at this point, as the patient will have a contrast enhanced thorax/abdomen CT for tumour identification, full staging and intervention planning, and an additional ultrasound scan would therefore, be unnecessary unless the patient has an iodinated contrast allergy. In some cases where the enhancement of a lesion is not so clear cut on CT or MRI, CEUS may problem solve owing to its real time imaging capability throughout all the contrast phases.

Many detected small solid renal masses will be benign, and among those that are malignant, not all subtypes behave the same, and some are more aggressive than others. Knowing the precise subtype allows for better planning of surveillance and treatment. Most renal masses can be evaluated and characterized accurately using CT. As a result, when a renal mass is diagnosed with confidence, appropriate management can be planned without further investigation.

Tumours larger than 3 cm, as in this case, are most often either isoechoic (49%) or mildly hyperechoic (33%), with only 4% found to be very hyperechoic (Sidhar, K. and McGahan, J.P. et al.,2016).

Macroscopic calcification may be seen in 8-18% of RCCs. Central calcification is seen in 87% of all malignant tumours (Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al., 2011). The use of doppler in RCC ultrasound may detect high tumour vascularity, however the absence of high frequency doppler shift does not exclude malignancy (Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al., 2011).

Compared to CT and MRI, ultrasound is a simple and safe examination, very cost effective, non-invasive, and contrary to CT gives no ionising radiation exposure to patients (Moloney, F. and Murphy, K.P et al., 2014 + O’Neill, W.C., 2014). However, ultrasound has limitations such as being less sensitive in detecting small renal masses < 3 cm (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010) as well as being highly operator dependent and sensitive to bowel gas and patient’s body habitus (Lema, P.C and Kim, J.H et al., 2017). The latter reference refers to an article in the Journal of vascular diagnostics and interventions about pitfalls and limitations when scanning the abdominal aorta. However, the limitations, such as bowel gas, operator dependence etc. are typical for ultrasound in general.

In the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma, updated in 2019, MRI and CEUS are both recommended to evaluate unclear cystic lesions, especially Bosniak III cysts, as MRI and CEUS in these cases show higher sensitivity and specificity than CT (Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al., 2019). Hence, ultrasound can be useful in characterizing whether a lesion is likely to be cystic and benign e.g. a hyperdense cyst is found on a non-contrast CT. It could also be utilised in cases where iodinated contrast media is contraindicated, as the most important criteria for differentiating malignancy in solid renal masses, according to the above urology guidelines, is the presence of contrast enhancement or restriction of fluid on MRI diffusion weighted imaging (Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al., 2019).

Although ultrasound plays a great role in incidental findings of RCC during routine abdominal examinations (Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al., 2018 + Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017) and in differentiating between solid and cystic renal masses as well as CEUS being helpful in specific cases providing information about vascularity, ultrasound imaging has limitations in further characterisation of solid tumours as well as staging of malignancy (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010).

Leveridge et al. refers to a study which claims that CEUS can be employed in staging of RCC, with CT and ultrasound being almost equivalent for predicting the T-stage (Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al., 2010).

The stage of RCC is usually reported using the tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification. This is based on the extent of the primary tumour (T), whether lymph nodes are affected (N) and whether metastases are present (M) (Knipe, H and Maller, V. et al., 2018). Therefore, even if CEUS is useful for predicting T-stage, the M and N stage will still need to be predicted. This leaves the use of CEUS for full staging inadequate.

In evaluation of renal masses, the main goals are to detect and classify the lesion (Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017). The primary criterion for diagnosing RCC is the identification of contrast enhancement and assessment of the tumour vascularity which can be used in suggesting a specific subtype of RCC. For a potential surgical and/or ablation intervention, accurate tumour staging, and information about renal vascular anatomy must be obtained (Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017).

There is a wide agreement that CT is the first line modality for staging of locoregional and suspected metastatic disease (Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al., 2018 + Diaz de Leon, A. and Pedrosa, L., 2017 + Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al., 2018). Later on, the pattern of contrast enhancement of the tumour on CT can be used as a good indicator of treatment success (Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al., 2018). Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to use CEUS for T-staging at this point, as the patient will have a contrast enhanced thorax/abdomen CT for tumour identification, full staging and intervention planning, and an additional ultrasound scan would therefore, be unnecessary unless the patient has an iodinated contrast allergy. In some cases where the enhancement of a lesion is not so clear cut on CT or MRI, CEUS may problem solve owing to its real time imaging capability throughout all the contrast phases.

Many detected small solid renal masses will be benign, and among those that are malignant, not all subtypes behave the same, and some are more aggressive than others. Knowing the precise subtype allows for better planning of surveillance and treatment. Most renal masses can be evaluated and characterized accurately using CT. As a result, when a renal mass is diagnosed with confidence, appropriate management can be planned without further investigation.

6References

1. Knipe, H and Maller, V. et al., 2018. Renal cell carcinoma (TNM staging). (online) Available at https://radiopaedia.org/articles/renal-cell-carcinoma-tnm-staging?lang=us

2. Knipe, H. and Asadov, R. et al. (2019) Renal Cell Carcinoma. Radiopaedia. (online) Available at https://radiopaedia.org/articles/renal-cell-carcinoma-1?lang=us

3. Lema, P.C and Kim, J.H et al., 2017. Overview of common errors and pitfalls to avoid in the acquisition and interpretation of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal aorta. Journal of vascular diagnostics and interventions. (online)Available at https://www.dovepress.com/overview-of-common-errors-and-pitfalls-to-avoid-in-the-acquisition-and-peer-reviewed-article-JVD

4. Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al. (2010) Imaging renal cell carcinoma with ultrasonography, CT and MRI. A nature research journal. (online) Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/nrurol.2010.63

5. Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al. (2019) European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2019 Update. European Urology. (online) Available at https://www.europeanurology.com/article/S0302-2838(19)30152-6/fulltext

6. Moloney, F. and Murphy, K.P et al. (2014) Haematuria: An Imaging Guide. Advances in urology. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124848/pdf/AU2014-414125.pdf

7. O’Neill, W.C. (2014) Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasound in Kidney Disease and Nephrology Procedures. Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3913230

8. Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al. (2018) Imaging for the diagnosis and response assessment of renal tumours. World Journal of Urology. (online) Available at https://www.europeanurology.com/article/S0302-2838(19)30152-6/fulltext

9. Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al. (2011) Diagnostic Ultrasound.4Th edition. Philadelphia: Mosby inc. Elsevier.

10. Sidhar, K. and McGahan, J.P. et al. (2016) Renal Cell Carcinoma: Sonographic appearance depending on size and histologic type. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine: Official journal of American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26740493

11. The Society and College of Radiographers and The British Medical Ultrasound Society (SCoR and BMUS) (2018) Guidelines for professional ultrasound practice. (online) Available at https://www.bmus.org/policies-statements-guidelines/professional-guidance/guidelines-for-professional-ultrasound-practice/

12. Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al. (2018) Imaging in Suspected Renal-Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30528378

13. West Midlands Expert Advisory Group for Urological Cancer (2016). Guidelines for the Management of Renal Cancer. NHS England. (online) Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids-east/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/05/guidelines-for-the-management-of-renal-cancer.pdf

2. Knipe, H. and Asadov, R. et al. (2019) Renal Cell Carcinoma. Radiopaedia. (online) Available at https://radiopaedia.org/articles/renal-cell-carcinoma-1?lang=us

3. Lema, P.C and Kim, J.H et al., 2017. Overview of common errors and pitfalls to avoid in the acquisition and interpretation of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal aorta. Journal of vascular diagnostics and interventions. (online)Available at https://www.dovepress.com/overview-of-common-errors-and-pitfalls-to-avoid-in-the-acquisition-and-peer-reviewed-article-JVD

4. Leveridge, M.J and Bostrom, P.J. et al. (2010) Imaging renal cell carcinoma with ultrasonography, CT and MRI. A nature research journal. (online) Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/nrurol.2010.63

5. Ljungberg, B. and Albiges, L. et al. (2019) European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2019 Update. European Urology. (online) Available at https://www.europeanurology.com/article/S0302-2838(19)30152-6/fulltext

6. Moloney, F. and Murphy, K.P et al. (2014) Haematuria: An Imaging Guide. Advances in urology. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124848/pdf/AU2014-414125.pdf

7. O’Neill, W.C. (2014) Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasound in Kidney Disease and Nephrology Procedures. Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3913230

8. Rossi, S.H. and Prezzi, D. et al. (2018) Imaging for the diagnosis and response assessment of renal tumours. World Journal of Urology. (online) Available at https://www.europeanurology.com/article/S0302-2838(19)30152-6/fulltext

9. Rumack, C. and Wilson, S.R. et al. (2011) Diagnostic Ultrasound.4Th edition. Philadelphia: Mosby inc. Elsevier.

10. Sidhar, K. and McGahan, J.P. et al. (2016) Renal Cell Carcinoma: Sonographic appearance depending on size and histologic type. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine: Official journal of American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26740493

11. The Society and College of Radiographers and The British Medical Ultrasound Society (SCoR and BMUS) (2018) Guidelines for professional ultrasound practice. (online) Available at https://www.bmus.org/policies-statements-guidelines/professional-guidance/guidelines-for-professional-ultrasound-practice/

12. Vogel, C. and Ziegelmüller, B. et al. (2018) Imaging in Suspected Renal-Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. (online) Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30528378

13. West Midlands Expert Advisory Group for Urological Cancer (2016). Guidelines for the Management of Renal Cancer. NHS England. (online) Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids-east/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/05/guidelines-for-the-management-of-renal-cancer.pdf