- European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology ~ Educating all for competence to practice ultrasound safely

GIUS

September 13, 2018Paediatric CEUS

October 30, 2018Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess

Dr. Serghei Puiu, Dr, PhD, Department of Radiology and Imaging, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicoale Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

Prof. Dr. Valentin Friptu, MD, PhD, Head of Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Nr 1, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicoale Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

Corresponding author: Serghei Puiu Email: puiusv@yahoo.com

Prof. Dr. Valentin Friptu, MD, PhD, Head of Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Nr 1, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicoale Testemitanu”, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

Corresponding author: Serghei Puiu Email: puiusv@yahoo.com

1Case Report

A 56 year-old female was referred to our department due to large mass in left lower abdominal quadrant with preliminary diagnosis of ovarian invasive tumour. At the time presentation the patient did not show evident clinical signs of acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), only lower abdominal dull pain, some abdominal tenderness and purulent vaginal discharge. The patient was afebrile and did not get any blood test at that time. The acute pain has started several weeks ago, but a few days before presentation to our clinic, the pain intensity suddenly decreased, accompanied with abundant vaginal discharge.

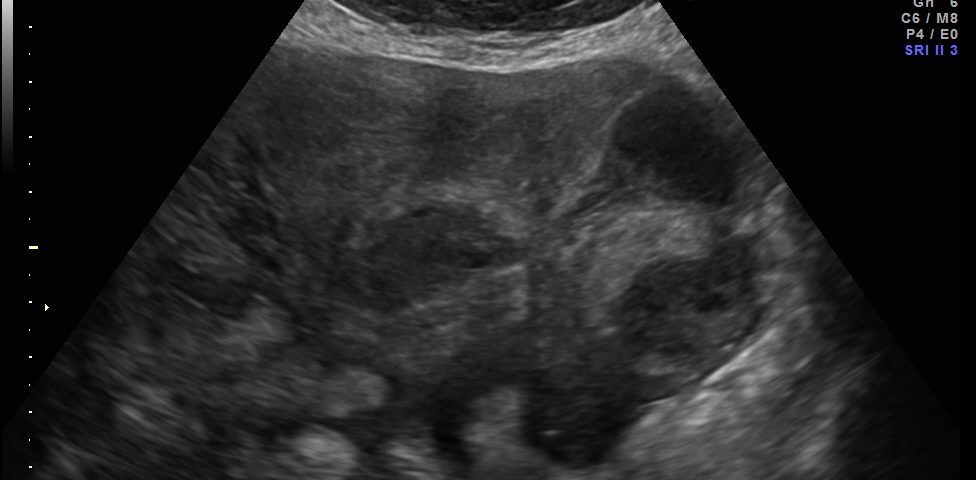

Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound scans were performed, which has shown the enlarged uterus with indistinct borders on the left side and a complex mass in left lower abdominal quadrant. A large irregular thick-walled, ill-defined multiloculated cystic/solid lesion with complex fluid collections and peripheral flow on color Doppler were seen. The anatomic distinction between the ovary and the fallopian tube could no longer be identified (Fig. 1). A tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) was presumed. Endovaginal sonogram showed a dilated uterine cavity and cervical canal, filled with heterogeneous, complex fluid and echogenic masses (Fig. 2a-c). An intrauterine contraceptive was detected. A cavity within myometrium with low-level internal echoes fluid also was revealed (Fig. 2c). This complex adnexal mass was adherent to uterus and a communication between TOA and the cavity within myometrium with fluid-debris level fluid was detected (Fig. 3a-b). This finding presumed a perforation of the TOA into uterus, due to myometrium necrosis, and spontaneous drainages into uterine cavity through myometrium. Increased echogenicity of the pelvic fat and a small amount of free fluid in cul-de sac also were seen. Fluid movements through fistula canal between TOA and uterine cavity were clearly seen when a gently pressure by ultrasound probe was applied (Video 1).

Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy was performed. The surgery confirmed presumed ultrasound findings. Any proof of adnexial neoplasm wasn’t revealed.

Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound scans were performed, which has shown the enlarged uterus with indistinct borders on the left side and a complex mass in left lower abdominal quadrant. A large irregular thick-walled, ill-defined multiloculated cystic/solid lesion with complex fluid collections and peripheral flow on color Doppler were seen. The anatomic distinction between the ovary and the fallopian tube could no longer be identified (Fig. 1). A tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) was presumed. Endovaginal sonogram showed a dilated uterine cavity and cervical canal, filled with heterogeneous, complex fluid and echogenic masses (Fig. 2a-c). An intrauterine contraceptive was detected. A cavity within myometrium with low-level internal echoes fluid also was revealed (Fig. 2c). This complex adnexal mass was adherent to uterus and a communication between TOA and the cavity within myometrium with fluid-debris level fluid was detected (Fig. 3a-b). This finding presumed a perforation of the TOA into uterus, due to myometrium necrosis, and spontaneous drainages into uterine cavity through myometrium. Increased echogenicity of the pelvic fat and a small amount of free fluid in cul-de sac also were seen. Fluid movements through fistula canal between TOA and uterine cavity were clearly seen when a gently pressure by ultrasound probe was applied (Video 1).

Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy was performed. The surgery confirmed presumed ultrasound findings. Any proof of adnexial neoplasm wasn’t revealed.

2Discussion

Tubo-ovarian abscess is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition and usually results as a complication of untreated or inadequately treated acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). PID refers to a spectrum of ascending acute infection of the upper genital tract and the surrounding structures in women. PID and its complications are found most commonly in reproductive age women and rarely in postmenopausal women. A series reported less than 2% TOA in postmenopausal women [1]. Lifetime prevalence of treatment among sexually experienced women aged 15–44 years is estimated at 5%, 2013 [2]. In the United States, PID accounts for approximately 80,000 initial visits to physicians’ offices among women aged 15–44 Years, 2014. It is still a frequent cause for emergency department visits [2, 3, 4].

A TOA is an inflammatory mass involving the fallopian tube, ovary, and, occasionally, other adjacent pelvic organs (bowel, bladder) [5]. Like PID, TOAs are also polymicrobial infections with a mixture of anaerobic, aerobic, and facultative organisms. Unlike PID, sexually transmitted pathogens are less common in TOAs [6, 7, 8]. Among hospitalized patients with PID approximately one third has TOA [9].

PID/TOA are usually the result of an ascending infection in the fallopian tubes causing pyosalpingitis, commonly (up to 75%) occurring during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle [10]. A high estrogen environment along with the presence of cervical ectopy found in adolescence facilitates the attachment of pathogens, which may contribute to the higher rates of PID among young women [11]. Douching, usage of intrauterine contraceptive device or gynecologic interventions may also predispose for spread of infection. Direct extension of infection from adjacent viscera and uterine instrumentation are more important risk factors in postmenopausal PID [12]. The purulent secretions can pass out of the tube adjacent to the ovary, eventually creating a walled-off complex fluid collection known as a primary TOA [13]. Less commonly, a TOA can also arise after infectious complications of gynecologic surgery, trauma and pregnancy related pelvic infection or direct spread from nearby inflammatory processes of the adjacent pelvic structures such as the appendix, colon, and bladder or in association with a pelvic malignancy. The term secondary TOA is often used [14, 15, 16].

During the acute stage, the dilated by purulent exudate fallopian tubes with thickened walls (5 mm or thicker) and endosalpingeal folds, presents specific ultrasonographic markers of salpingitis/pyosalpinx, as ‘cogwheel’ sign, ovoid/retort tubal shape, incomplete septa. Hyperemia of the fallopian tube walls is seen on color Doppler [17]. Some exudate and infectious pathogens may spill into the pelvis. The ovary may become involved by invasion of organisms through the ovulation site. Necrosis inside this complex mass may result in one or more abscess cavities [18].

Extent of ovarian involvement is defined as:

Tubo–ovarian complex: At this stage, the tube and ovary are still separately discernible structures within the inflammatory mass. Fallopian tube adheres to the ovary; the latter cannot be pushed apart (by vaginal probe). The inflammatory process may progress to its most severe phase: the tubo–ovarian abscess. Ultrasound image shows a total breakdown of the normal structure of the adnexa. The ovary and tube become confluent and cannot be separately distinguished within the inflammatory mass. Loculations, speckled fluid and motion tenderness are present. These two entities are not only sonographically distinct, but also clinically distinct and deserving of different therapeutic approaches [17]. It is important to note that TOAs, unlike other types of abscesses, occur between organs rather than confined inside an organ. The adherence of adjacent pelvic structures, such as the omentum and bowel, might serve a host defense mechanism to contain the inflammatory process within the pelvis. This could be a reason that some women with TOA are not overtly sick with an elevated white cell count or fever [19]. Following necrosis inside this complex mass may result in perforation in neighboring organs and tissues.

Early recognition of a TOA is important in order to prevent the associated morbidity and mortality as rupture and following sepsis. The clinical context is extremely important in interpretation. Lower abdominal pain and abnormal vaginal discharge are common symptoms. Additional symptoms of TOA include irregular vaginal bleeding (36%), urinary symptoms (19%) and proctitis symptoms (7%) [20]. Patients also typically present with fever and leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level. However, about 20% of patients with TOA may be afebrile or have a normal leukocyte count. Pain can also be dull, which can further confound the diagnosis [21, 22]. Ultrasound (US) is the initial imaging modality of choice in cases of PID/TOA. Occasionally, Computed Tomography (CT) and/or Magnetic Resonance (MR) scanning may be used as diagnostic study in cases in which the ultrasonographic findings are equivocal [23-26]. Ultrasound examination of TOA usually will show a multilocular complex adnexal structure with irregular thick walls, septations and internal echoes likely pus with cellular debris. [27]. Although the sonographic appearance of an adnexal mass can be highly suggestive of a TOA, there is often an overlap of appearances with other entities including endometriosis, hemorrhagic cysts, dermoid cysts or other malignant cystic ovarian masses [28, 29]. Therefore, a diagnosis of TOA often is difficult to make by sonography alone, a thorough history, clinical examination and laboratory findings can play a key role in diagnosis. Actual treatment modalities include broad spectrum antibiotic therapy, minimally-invasive ultrasound/radiological guided drainage procedures, invasive surgery, or combinations of these interventions.

Success rates of 67–75% of small to medium sized TOAs have been reported with prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics alone [30]. Abscess size greater than 8.0cm has been shown to be predictive of treatment failure with antibiotics alone. Thus, greater diameters or when clinical response is not achieved within 48 hours after initiation of antibiotics, then surgical management or drainage should be considered [31].

More recently, minimally invasive approaches to drainage of abscesses with concomitant use of antibiotics have become available. Success rates for imaging-guided drainage (US, CT or MR) have been reported by Gjelland et al. [32] as high as 93.4% and 94.7 % by Goharkhay et al. [33]

Surgical management should be first considered in postmenopausal women, because malignancy is a concern in any postmenopausal woman who presents with an abscess. Protopapas et al. reported that 47% postmenopausal women had an underlying malignancy [34].

A TOA is an inflammatory mass involving the fallopian tube, ovary, and, occasionally, other adjacent pelvic organs (bowel, bladder) [5]. Like PID, TOAs are also polymicrobial infections with a mixture of anaerobic, aerobic, and facultative organisms. Unlike PID, sexually transmitted pathogens are less common in TOAs [6, 7, 8]. Among hospitalized patients with PID approximately one third has TOA [9].

PID/TOA are usually the result of an ascending infection in the fallopian tubes causing pyosalpingitis, commonly (up to 75%) occurring during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle [10]. A high estrogen environment along with the presence of cervical ectopy found in adolescence facilitates the attachment of pathogens, which may contribute to the higher rates of PID among young women [11]. Douching, usage of intrauterine contraceptive device or gynecologic interventions may also predispose for spread of infection. Direct extension of infection from adjacent viscera and uterine instrumentation are more important risk factors in postmenopausal PID [12]. The purulent secretions can pass out of the tube adjacent to the ovary, eventually creating a walled-off complex fluid collection known as a primary TOA [13]. Less commonly, a TOA can also arise after infectious complications of gynecologic surgery, trauma and pregnancy related pelvic infection or direct spread from nearby inflammatory processes of the adjacent pelvic structures such as the appendix, colon, and bladder or in association with a pelvic malignancy. The term secondary TOA is often used [14, 15, 16].

During the acute stage, the dilated by purulent exudate fallopian tubes with thickened walls (5 mm or thicker) and endosalpingeal folds, presents specific ultrasonographic markers of salpingitis/pyosalpinx, as ‘cogwheel’ sign, ovoid/retort tubal shape, incomplete septa. Hyperemia of the fallopian tube walls is seen on color Doppler [17]. Some exudate and infectious pathogens may spill into the pelvis. The ovary may become involved by invasion of organisms through the ovulation site. Necrosis inside this complex mass may result in one or more abscess cavities [18].

Extent of ovarian involvement is defined as:

Tubo–ovarian complex: At this stage, the tube and ovary are still separately discernible structures within the inflammatory mass. Fallopian tube adheres to the ovary; the latter cannot be pushed apart (by vaginal probe). The inflammatory process may progress to its most severe phase: the tubo–ovarian abscess. Ultrasound image shows a total breakdown of the normal structure of the adnexa. The ovary and tube become confluent and cannot be separately distinguished within the inflammatory mass. Loculations, speckled fluid and motion tenderness are present. These two entities are not only sonographically distinct, but also clinically distinct and deserving of different therapeutic approaches [17]. It is important to note that TOAs, unlike other types of abscesses, occur between organs rather than confined inside an organ. The adherence of adjacent pelvic structures, such as the omentum and bowel, might serve a host defense mechanism to contain the inflammatory process within the pelvis. This could be a reason that some women with TOA are not overtly sick with an elevated white cell count or fever [19]. Following necrosis inside this complex mass may result in perforation in neighboring organs and tissues.

Early recognition of a TOA is important in order to prevent the associated morbidity and mortality as rupture and following sepsis. The clinical context is extremely important in interpretation. Lower abdominal pain and abnormal vaginal discharge are common symptoms. Additional symptoms of TOA include irregular vaginal bleeding (36%), urinary symptoms (19%) and proctitis symptoms (7%) [20]. Patients also typically present with fever and leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level. However, about 20% of patients with TOA may be afebrile or have a normal leukocyte count. Pain can also be dull, which can further confound the diagnosis [21, 22]. Ultrasound (US) is the initial imaging modality of choice in cases of PID/TOA. Occasionally, Computed Tomography (CT) and/or Magnetic Resonance (MR) scanning may be used as diagnostic study in cases in which the ultrasonographic findings are equivocal [23-26]. Ultrasound examination of TOA usually will show a multilocular complex adnexal structure with irregular thick walls, septations and internal echoes likely pus with cellular debris. [27]. Although the sonographic appearance of an adnexal mass can be highly suggestive of a TOA, there is often an overlap of appearances with other entities including endometriosis, hemorrhagic cysts, dermoid cysts or other malignant cystic ovarian masses [28, 29]. Therefore, a diagnosis of TOA often is difficult to make by sonography alone, a thorough history, clinical examination and laboratory findings can play a key role in diagnosis. Actual treatment modalities include broad spectrum antibiotic therapy, minimally-invasive ultrasound/radiological guided drainage procedures, invasive surgery, or combinations of these interventions.

Success rates of 67–75% of small to medium sized TOAs have been reported with prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics alone [30]. Abscess size greater than 8.0cm has been shown to be predictive of treatment failure with antibiotics alone. Thus, greater diameters or when clinical response is not achieved within 48 hours after initiation of antibiotics, then surgical management or drainage should be considered [31].

More recently, minimally invasive approaches to drainage of abscesses with concomitant use of antibiotics have become available. Success rates for imaging-guided drainage (US, CT or MR) have been reported by Gjelland et al. [32] as high as 93.4% and 94.7 % by Goharkhay et al. [33]

Surgical management should be first considered in postmenopausal women, because malignancy is a concern in any postmenopausal woman who presents with an abscess. Protopapas et al. reported that 47% postmenopausal women had an underlying malignancy [34].

3Conclusion

Tubo-ovarian abscess is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition and usually results as a complication of untreated or inadequately treated acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Extent of ovarian and fallopian involvement is defined as: tubo–ovarian complex and more severe stage: tubo–ovarian abscess. Early recognition of a TOA is important in order to prevent the associated morbidity and mortality. Although the sonographic appearance of an adnexal mass can be highly suggestive of a TOA, there is often an overlap of appearances with other adnexial masses. Therefore, a diagnosis of TOA often is difficult to make by sonography alone, a thorough history, clinical examination and laboratory findings can play a key role in diagnosis, especially in post-menopausal women, when inflammatory signs sometimes are not so evident.

4Figure Legends

Figure 1. Transabdominal scan. Enlarged uterus with indistinct borders on the affected side and a complex masses in left lower abdominal quadrant. Note a large thick-walled, ill-defined multiloculated cystic/solid lesion with complex fluid collections. The anatomic distinction between the ovary and the fallopian tube can no longer be identified.

Figures 2a-c. Endovaginal sonograms. Dilated uterine cavity and cervical canal, filled with heterogeneous, complex fluid and masses. An intrauterine contraceptive device also can be easily seen. Note the cavity within myometrium with low level internal echoes fluid and a fluid-fluid level on figure 2c.

Figures 3a-b. Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound scans. A complex adnexal mass adheres to uterus and a communication (fistula) between TOA and a cavity within myometrium and then into endometrial cavity with low level echoes fluid is clearly seen. Increased echogenicity of the pelvic fat and a small amount of free fluid in cul-de sac also can be seen.

Video 1. Transvaginal scan. Fluid movements through fistula canal between TOA and uterine cavity are clearly seen when a gently pressure by ultrasound probe is applied.

Figures 2a-c. Endovaginal sonograms. Dilated uterine cavity and cervical canal, filled with heterogeneous, complex fluid and masses. An intrauterine contraceptive device also can be easily seen. Note the cavity within myometrium with low level internal echoes fluid and a fluid-fluid level on figure 2c.

Figures 3a-b. Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound scans. A complex adnexal mass adheres to uterus and a communication (fistula) between TOA and a cavity within myometrium and then into endometrial cavity with low level echoes fluid is clearly seen. Increased echogenicity of the pelvic fat and a small amount of free fluid in cul-de sac also can be seen.

Video 1. Transvaginal scan. Fluid movements through fistula canal between TOA and uterine cavity are clearly seen when a gently pressure by ultrasound probe is applied.

5References

- Heaton FC, Ledger WJ. Postmenopausal tuboovarian abscess. Obstet Gynecol. 1976 Jan. 47(1):90-4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Statistics. Updated October 26, 2016. MedlinePlus. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/PID/stats.htm. (Visited 14.12. 2016)

- Ross J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. BMJ. 2001 Mar 17. 322(7287):658-9.

- Ness RB, Smith KJ, Chang CC, Schisterman EF, Bass DC. Prediction of pelvic inflammatory disease among young, single, sexually active women.

- Granberg S, Gjelland K, Ekerhovd E. The management of pelvic abscess. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 23:667.

- Jaiyeoba O, Lazenby G, Soper DE. Recommendations and rationale for the treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:61–70.

- Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2039.

- Hook EW III, Handsfield HH. Gonococcal infections in the adult. Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, et al, (editors). Sex Transm Dis. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. 627-45.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). http://www.cdc.gov/std/pid/stats.htm (Visited 14.12. 2016).

- Eschenbach DA. Acute pelvic inflammatory disease: etiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1976;19:147–169.

- Westrom L. Incidence, prevalence, and trends of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in industrialized countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:880–892.

- Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Tubo-ovarian abscess in post-menopausal patients. South Med J. 1992. 85:696-699.

- Callen PW. Ultrasound characteristics of pelvic inflammatory disease. Ultrasonography in obstetrics and genecology. (Fifth edition) 2008;30:974.

- Potter AW, Chandrasekhar CA. US and CT Evaluation of Acute Pelvic Pain of Gynecologic Origin in Nonpregnant Premenopausal Patients. RadioGraphics. 2008;28:1645–1659.

- Morishita K, Gushimiyagi M, Hashiguchi M, Stein GH, Tokuda Y. Clinical prediction rule to distinguish pelvic inflammatory disease from acute appendicitis in women of childbearing age. Am J Emerg Med. 2007 Feb. 25(2):152-7.

- Eshed I, Halshtok O, Erlich Z, et al. Differentiation between right tubo-ovarian abscess and appendicitis using CT-a diagnostic challenge. Clin Radiol. 2011 Nov.66(11):1030-5.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Lerner JP, Monteagudo A, Murphy KE, Heller DS. Transvaginal sonographic markers of tubal inflammatory disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul. 12(1):56-66.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL. Progress in the management of tuboovarian abscesses. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:433–444.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL. Progress in the management of tuboovarian abscesses. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:433–444.

- Crossman SH. The challenge of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Mar 1. 73(5):859-64

- Kim SH, Kim SH, Yang DM, Kim KA. Unusual causes of tubo-ovarian abscess: CT and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2004 Nov-Dec;24(6):1575–89

- Beigi RH, Wiesenfeld HC. Pelvic inflammatory disease: new diagnostic criteria and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003 Dec. 30(4):777-93

- Jung SI, Kim YJ, Park HS, Jeon HJ, Jeong KA. Acute pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnostic performance of CT. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011 Mar. 37(3):228-35.

- Thomassin-Naggara I, Darai E, Bazot M. Gynecological pelvic infection: what is the role of imaging?. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012 Jun. 93(6):491-9.

- Kim SH, Kim SH, Yang DM, Kim KA. Unusual causes of tubo-ovarian abscess: CT and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2004 Nov-Dec;24(6):1575–89.

- Lee DC, Swaminathan AK. Sensitivity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of tubo-ovarian abscess: a case report and literature review. J Emerg Med. 2011 Feb. 40(2):170-5.

- Anjali Agrawal et al. Imaging in Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-Ovarian Abscess. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/404537-overview. Updated: Feb 27, 2015. (Visited 05.12.2016)

- Kim SH, Kim SH, Yang DM, Kim KA. Unusual causes of tubo-ovarian abscess: CT and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2004 Nov-Dec;24(6):1575–89.

- Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Jr Endometriosis: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics. 2001;21:193–216.

- Mirhashemi R, Schoell WM, Estape R, Angioli R, Averette HE. Trends in the management of pelvic abscesses. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 188: 567–572.

- Dewitt J, Reining A, Allsworth JE, et al. Tuboovarian abscesses: is size associated with duration of hospitalization & complications? Obstet Gynecol Int. 2010;2010:847041. doi: 10.1155/2010/847041. Epub 2010 May 24.

- Gjelland K, Ekerhovd E, Granberg S. Transvaginal ultrasound guided aspiration for treatment of tubo-ovarian abscess: a study of 302 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193: 1323–1330.

- Goharkhay, U. Verma and F. Maggiorotto. Comparison of CT- or ultrasound-guided drainage with concomitant intravenous antibiotics vs. intravenous antibiotics alone in the management of tubo-ovarian abscesses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 29: 65–69

- Protopapas AG, Diakomanolis ES, Milingos SD, et al. Tubo-ovarian abscesses in postmenopausal women: gynecological malignancy until proven otherwise? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:203–209.

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig1.jpg)

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig2a.jpg)

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig2b.jpg)

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig2c.jpg)

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig3a.jpg)

![Unusual case of uterine perforation by a tubo-ovarian abscess </br> [Sep 2018]](https://efsumb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cotm_sept2018_fig3b.jpg)